Liza Dimbleby

April 2nd to April 9th

///cheeses.quarrel.poorly is the WHAT3WORDS location of Peedie Sands in Caithness, Scotland.

58°40′21″N03°22′31″W

January 16th to January 23rd

January 9th to January 16th

December 12th to December 19th

December 5th to December 12th

November 28th to December 5th

November 14th to November 21st

October 23rd to October 31st

Letter from Glasgow: The Forgotten Music

I was in a charity shop with my daughter, rummaging among old coats at the end of the rail. Suddenly a song came on — a song I knew once but hadn’t heard for ages, it was sort of Northern Soul but it soared with a refrain that came back three times and felt like free-wheeling, soaring to the edge of a landscape. It thrilled me. It gave generously. I was surprised how good it felt to be away from my desk, chancing on songs amongst old clothes. I went to the counter and paid a few pounds for a striped sheet, a check tablecloth and a cellular wool blanket, the song was free.

We left the shop and were walking along the pavement when I realised that I couldn’t recall the song. The strength was not its words but the tune without words and I could not hook it back in. I wondered how to find it this song without words, without a title. How could I remember it?

We went to a performance at a gallery, where daubed canvases were raised on pulleys and women were rolled up and falling out of them, to a soundtrack of looped scrapes and cries. After the earnest discussion that followed we left the gallery. Just before we left, as I was washing my hands at the toilets, the song came bouncing back to me.. All of it. I was so happy, there it was inside me and it had decided to return to me, to cheer me along. I stepped out onto the pavement humming my song. At the bottom of a stone stairwell we stopped and I sang it to my daughter’s phone, as people passed by, to an app that recognises tunes, but to no avail. The app stayed blank and pulsing. So I kept on singing as we walked through the city to meet my friend. My daughter sang me a line of Bach back, we made a song between the two, call and response. We crossed the road, my friend was waving to us, and then suddenly — the song was gone! It had vanished as subtly as it appeared, and I had no trace of it. I kept trying, but all I got were the more obvious, less brilliant, tunes of the era. This one was not mine to summon. I had not heard it for so many years and now I didn’t know when I would hear it again. I had no clues by which to bring it back.

I think about it inside me, biding its time, resisting my call for it — this song that so delighted me, that returned to me twice, unbidden, yesterday, and then went on its way, went back inside me, perhaps never to return. When it was there I wanted to carry it, be carried by it. I did not think of recording the notes, making a digital imprint by which to catch and hold it. I thought that it was a part of me, that it would last forever. Now I’m waiting, wondering where within me it is hiding.

October 10th to October 17th

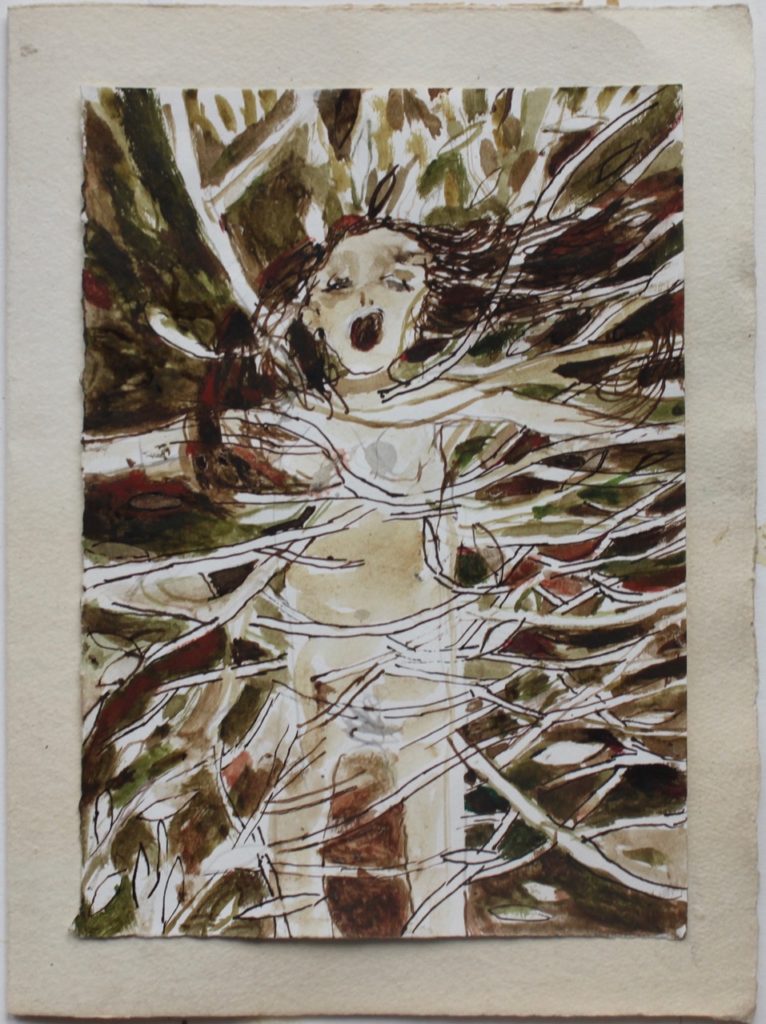

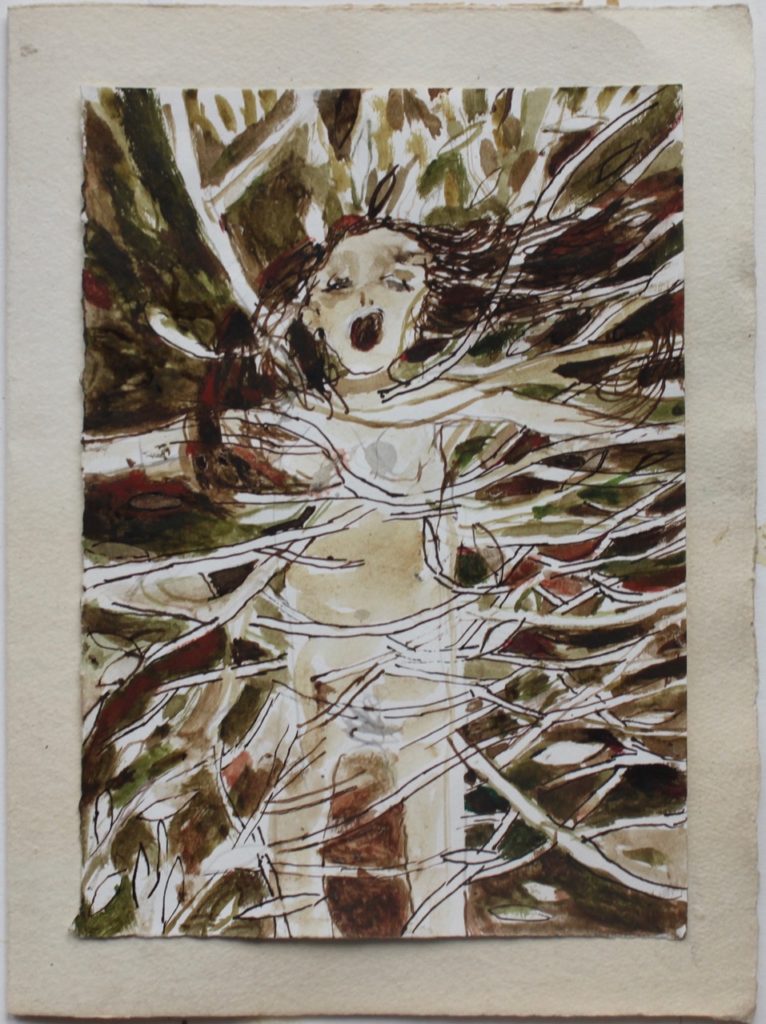

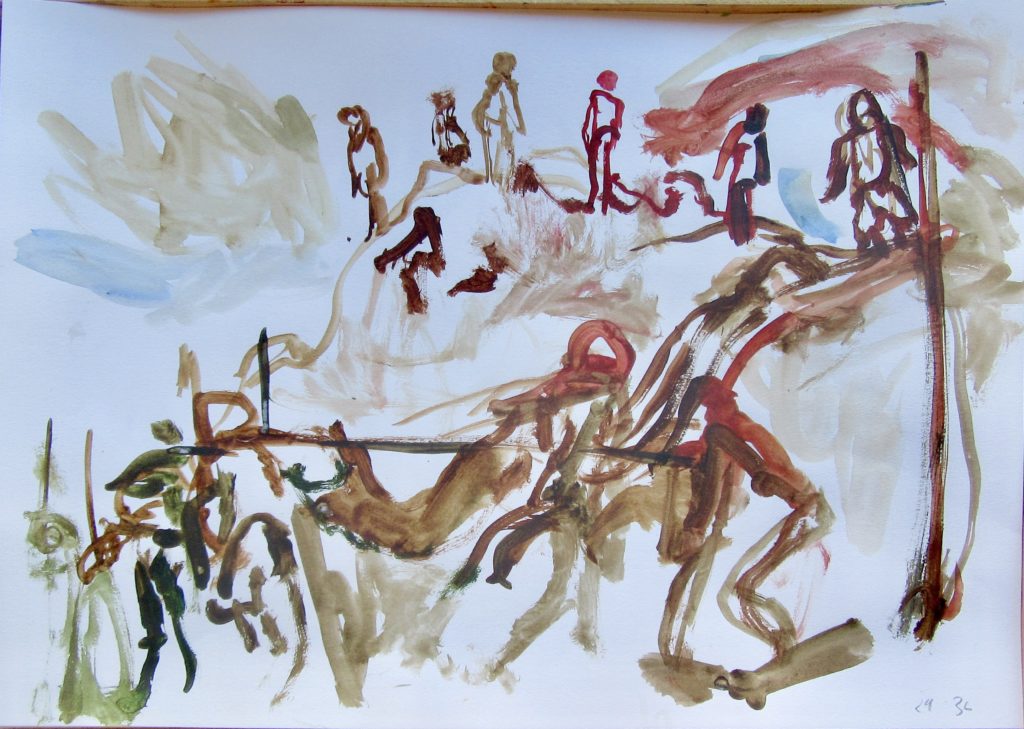

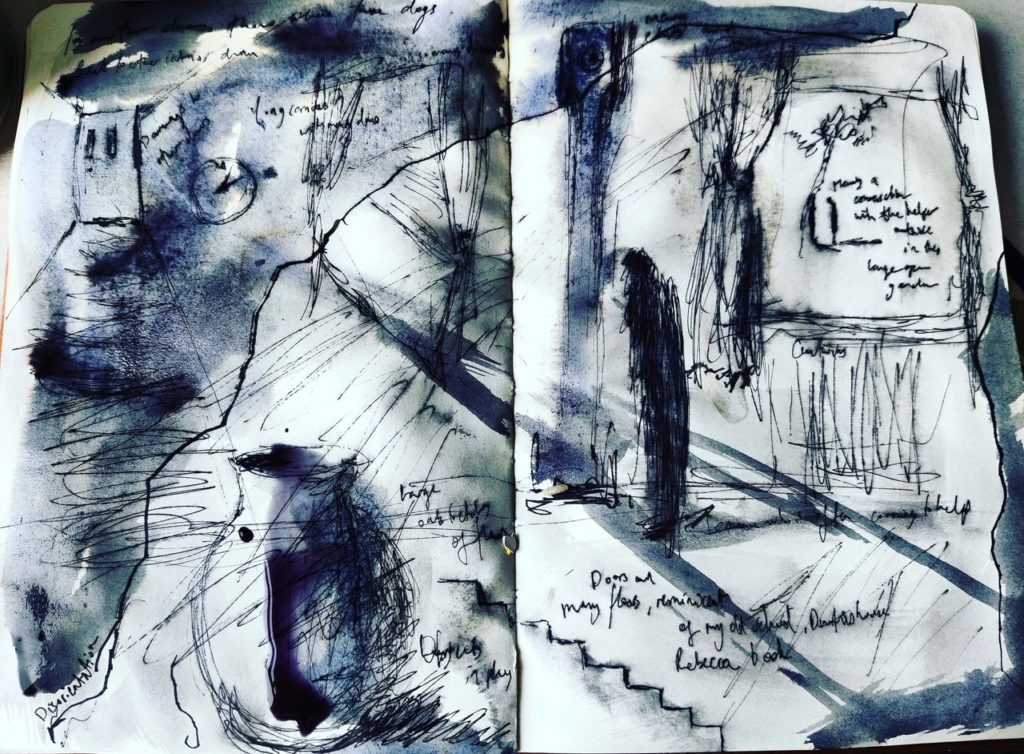

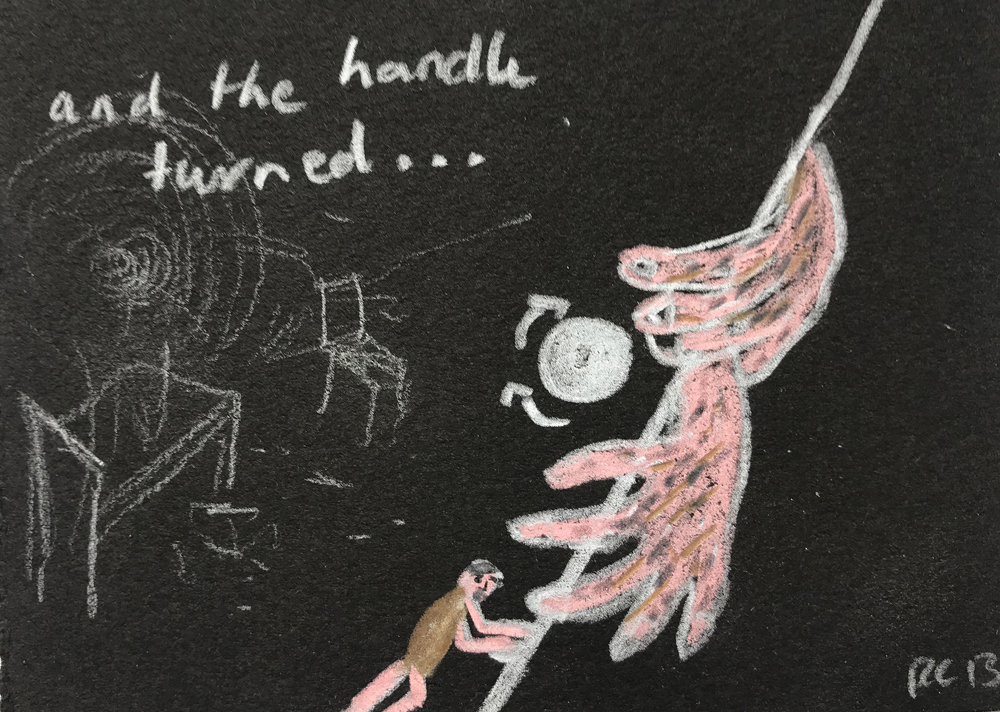

Letter from Glasgow: L’ Avenir au Bois Dormant or Philomela’s Cry

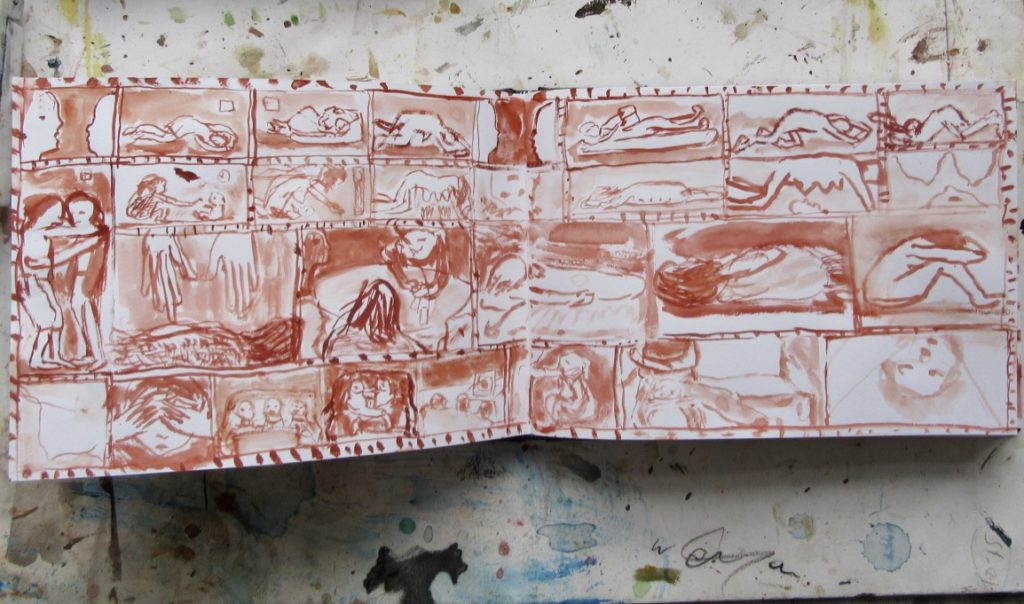

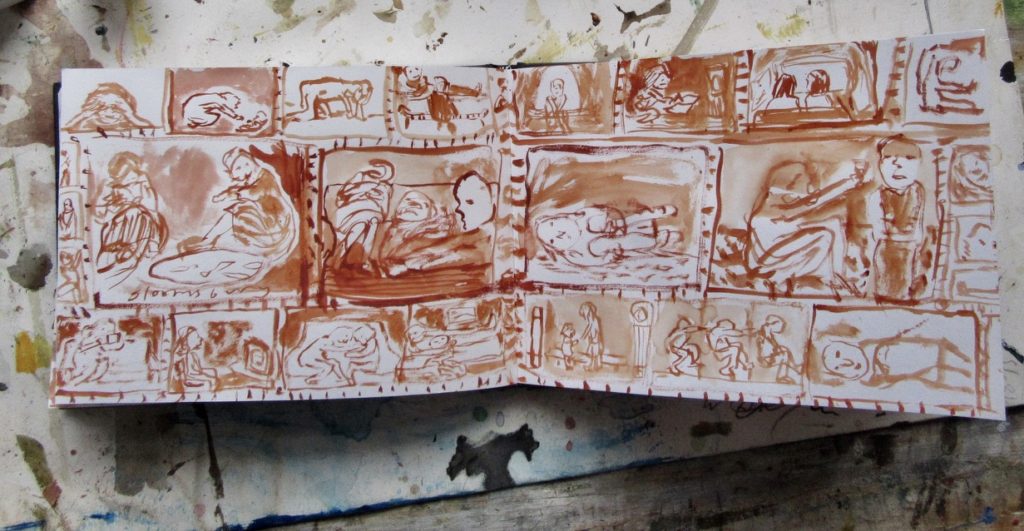

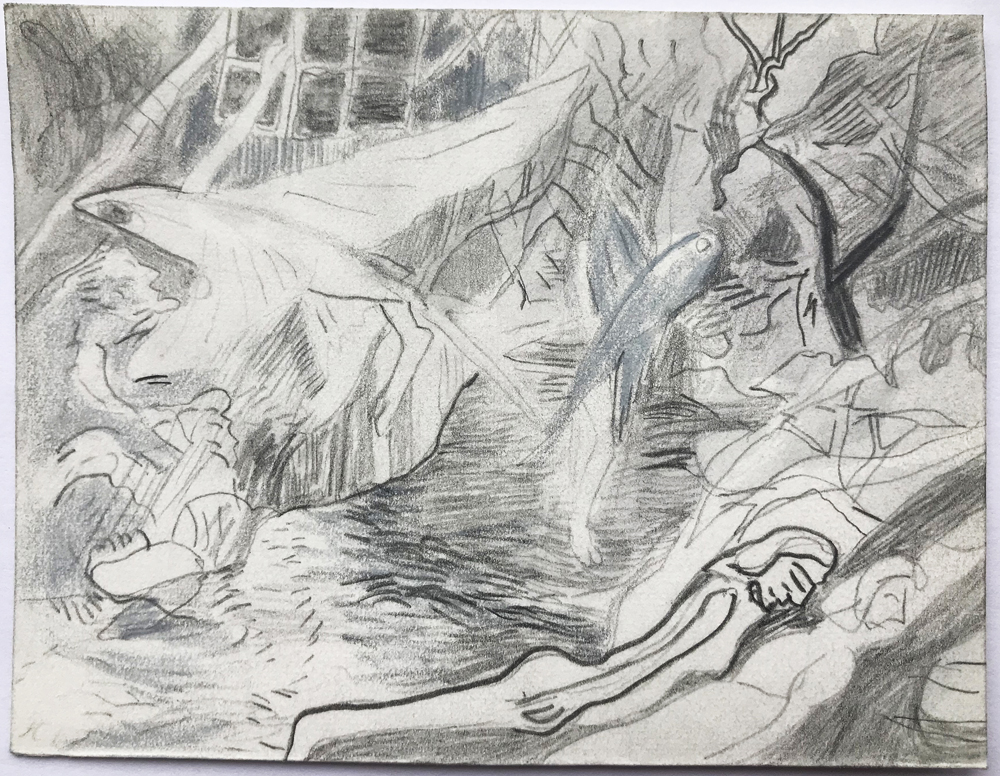

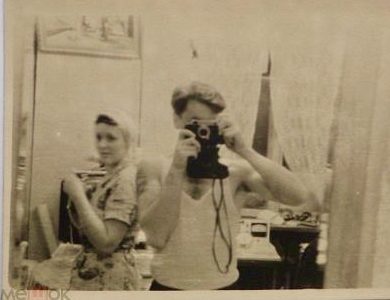

I spent much of the summer sorting — endless piles of paper, scrawled pages of notes and beginnings, false starts and interruptions, and hundreds of rolls of drawings that had been stored in an attic, unseen for thirty years. It was so hot in the small space that I unfurled the scrolls in my underwear and soon became trapped inside them, submerged by these unruly curls and screeds of yellowed paper, that sprung out and fast piled up about my body and over my head — a snaking chaos inscribed with thousands of drawings. I was afraid of not being able to escape and tore through some in my efforts to disentangle. When I managed to unravel myself, what surprised me was the consistency of the impulse that drove these inscriptions. My concerns, my reasons for marking paper at all, have not changed much. The difference is that thirty years ago I might have thought that all this restless writing and drawing would add up to something like an answer — that would prove ultimately freeing, and allow me to step out into a brave new and resonant world. I no longer expect this, and I let my drawings lie dormant. The violence of their release, their still-aliveness, took me by surprise.

I dreamed that I was standing in a group, we were playing chamber music. It was my turn to join the sound. I began my note, I knew the music. I thought, this may sound dissonant but soon it will find its place, it will join with the notes of the other players, we will find our harmony and be carried forth in one continuous many-layered sound. Together, we will sound. I opened my mouth. But my note jarred loud and uncomfortably discordant against the others, and I could not shift it. The sound came from my mouth but it was rough and plangent, it would not join the tune. I thought of the musical term stringendo which suggests not actual strings, nor stridency but rather an urgency, a gripping or tightening, a rushing towards the end, even a strangling.

Will we still want to dance tomorrow? It depends on what music is playing.

October 3rd to October 10th

Will we still want to dance tomorrow? It depends on what music is playing.

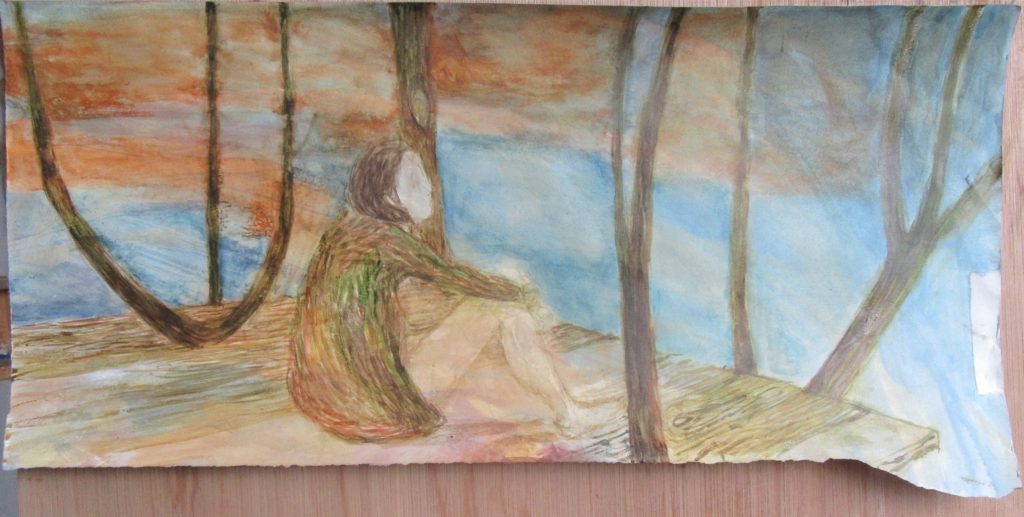

Dancing Oak, Glasgow 2023

That evening, when I had finished the drawing, I walked down the hill by my house. I stopped by a tree at the bottom of the hill. A tall oak, with arms raised up as if in greeting. Exultant. You could not hide in this one’s skirts, but her head is almost heart shaped.

Darach — the Celtic name for oak, or oak grove

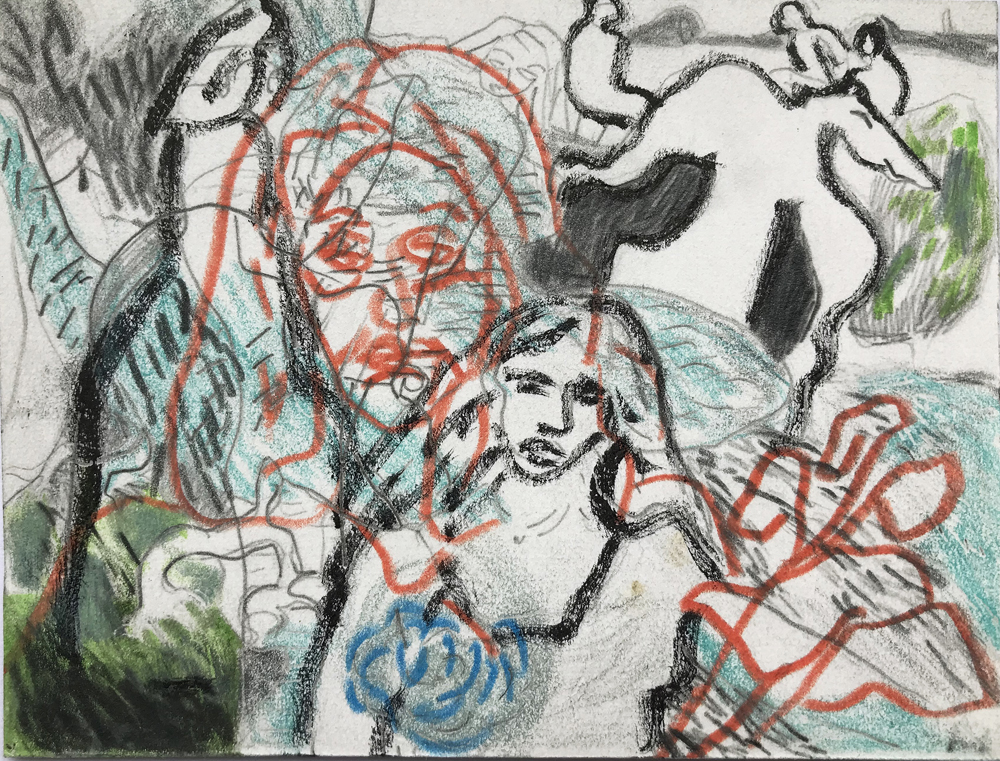

She seemed to see all the oaks around her dancing, their lightning fork branches fizzing outwards with life.

My tree seemed to grow arms

how wonderful these oak trees were — like being hidden under your mother’s skirts

We sat under that huge skirt and were sheltered, a short while, from the future, as we looked across the field.

September 12th to September 19th

July 25th to August 1st

Letter from Glasgow: Living Oaks

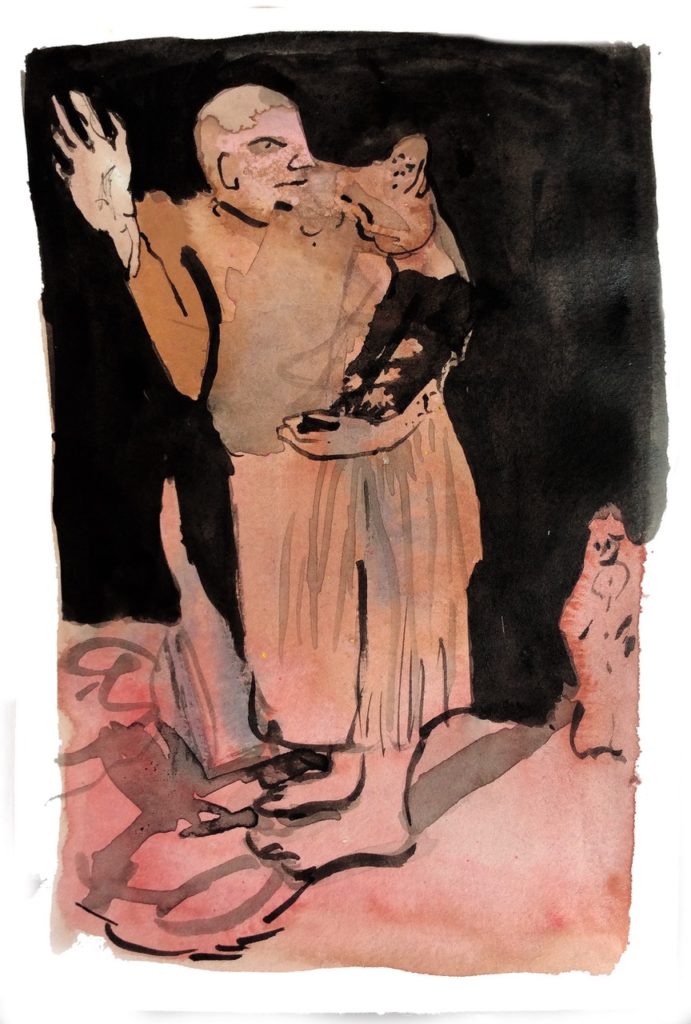

Last month I went to visit my uncle in Devon. He is a sculptor, the only artist on my father’s side of the family, and he has always been important to me, a person who goes about things differently from his broadcasting brothers, an ally in the family fray. He showed me another way of speaking and thinking, and he works with clay. I used to model for him as a teenager, complex three-quarter reliefs, for which I often had to suspend my arm on a rope, but as I sat for him in his studio on long hot midsummer days we would talk about many things that I could not find words for, was unable to articulate, at home. We would spin metaphors back and forth as we tried to get closer to the oddities of experience. I relished his mixture of wit and awe, his willingness to risk pretension in our wayward speculations about what art might do, while remaining alert against snobbery or pomposity, attentive to ordinary pleasures — of family meals, or the light on the trees outside the window.

Now he is very ill, and I made this visit in urgency and trepidation. I did not know how long he would have energy to see me for but we spent all of Midsummer’s Day together, with his family. We ate lunch outside, at a trestle table under one of the huge oak trees that surround his house. He reminded me how wonderful these oak trees were — like being hidden under your mother’s skirts, he said, as we sat at the table. We sat under that huge skirt and were sheltered, a short while, from the future, as we looked across the field.

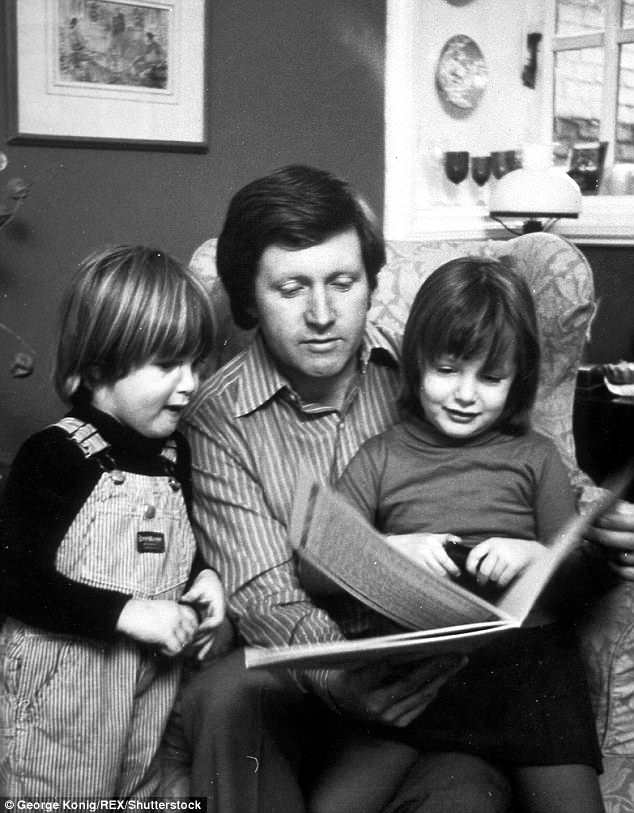

On my way home I went to visit some friends in London, a mutual artist friend of ours had died the day before, they had been close to him for years. I sat at their kitchen table and noticed how alive the drawing on the wall behind was. It was a large framed pencil drawing, made by the artist who died, Peter Darach. His line is distinctive, nerved and almost in motion, a line of imaginative vibrancy and conviction, unlike any other — it takes you into his world. I was not surprised to see the drawing reverberate as it did, if Darach’s spirit was hovering anywhere in these limbo days just after his death, it would be in his drawings. He was an artist recluse, had almost never exhibited, but had lived modestly on the outskirts of London, moving further out from the centre to raise funds against the escalating property prices when it proved necessary, and had brought his two sons up alone after the death of his wife.

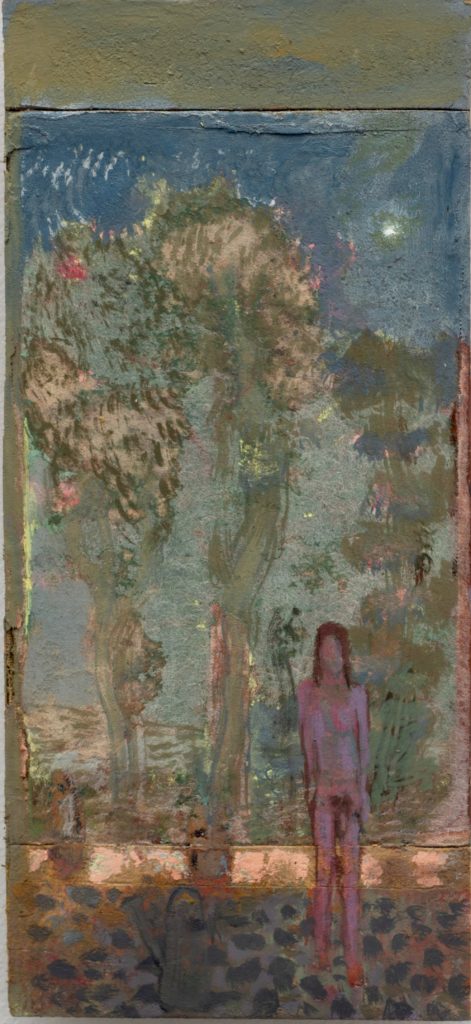

Peter had changed his surname long ago to Darach — the Celtic name for oak, or oak grove. He was keen on Celtic mythology and lore. His conviction about art, of its mysterious spiritual power, was catching. His sons had asked for friends to make drawings or write messages on paper, to be stuck in a sort of collage on to his cardboard coffin before the burial. I realised that my drawing would need to be a tree. Not the birch trees I have been making paintings of, laid out like dead men on family dining tables, but the broad oak, something upright and living, and powerful, and of course because Peter himself had chosen the oak for his name.

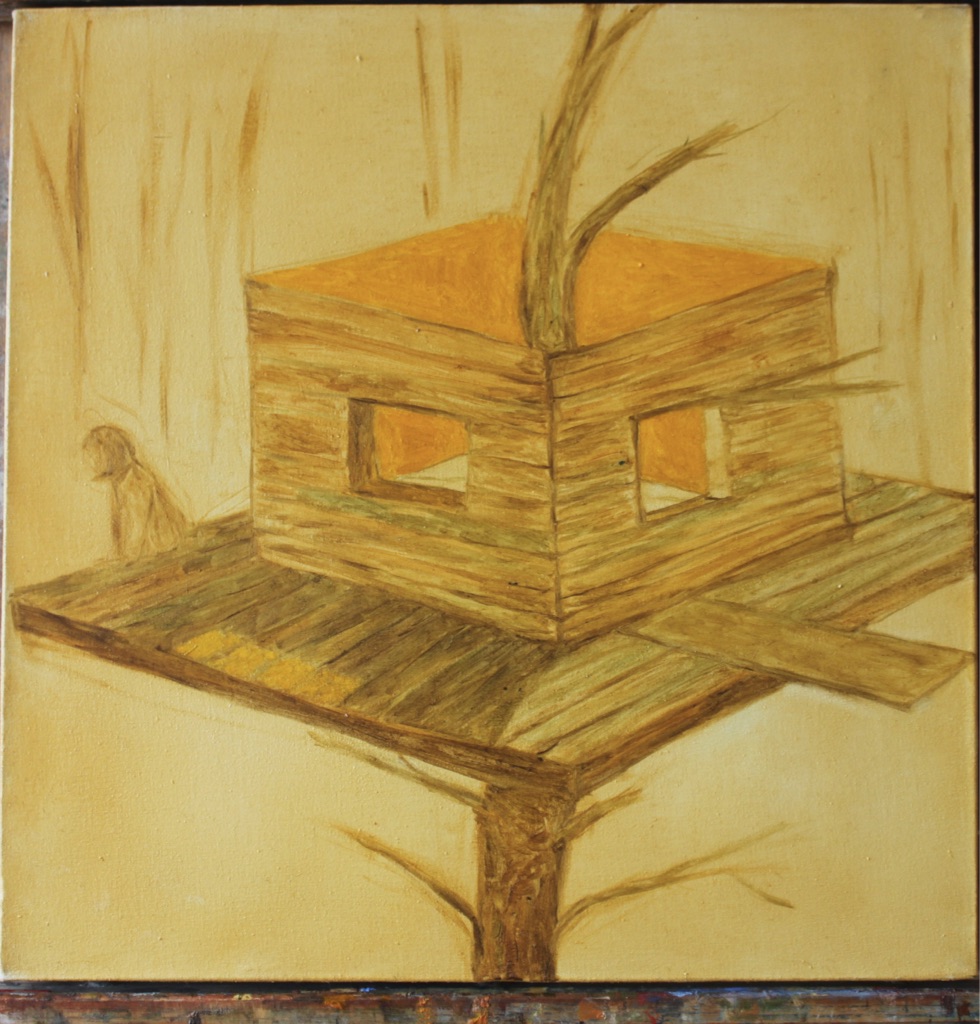

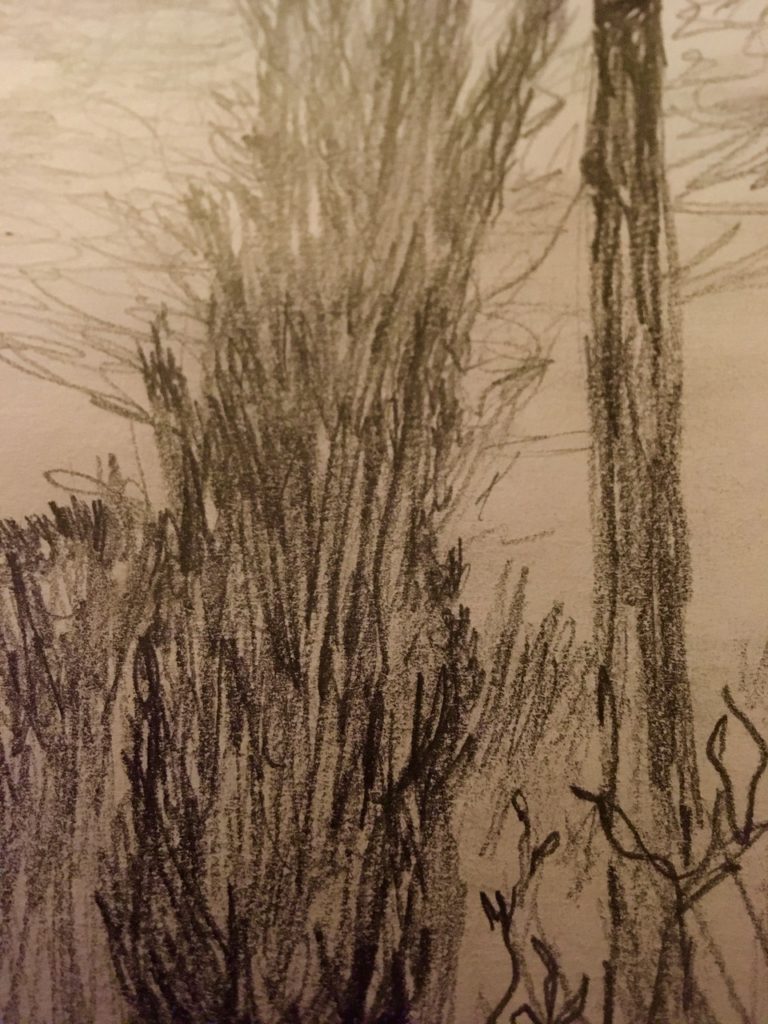

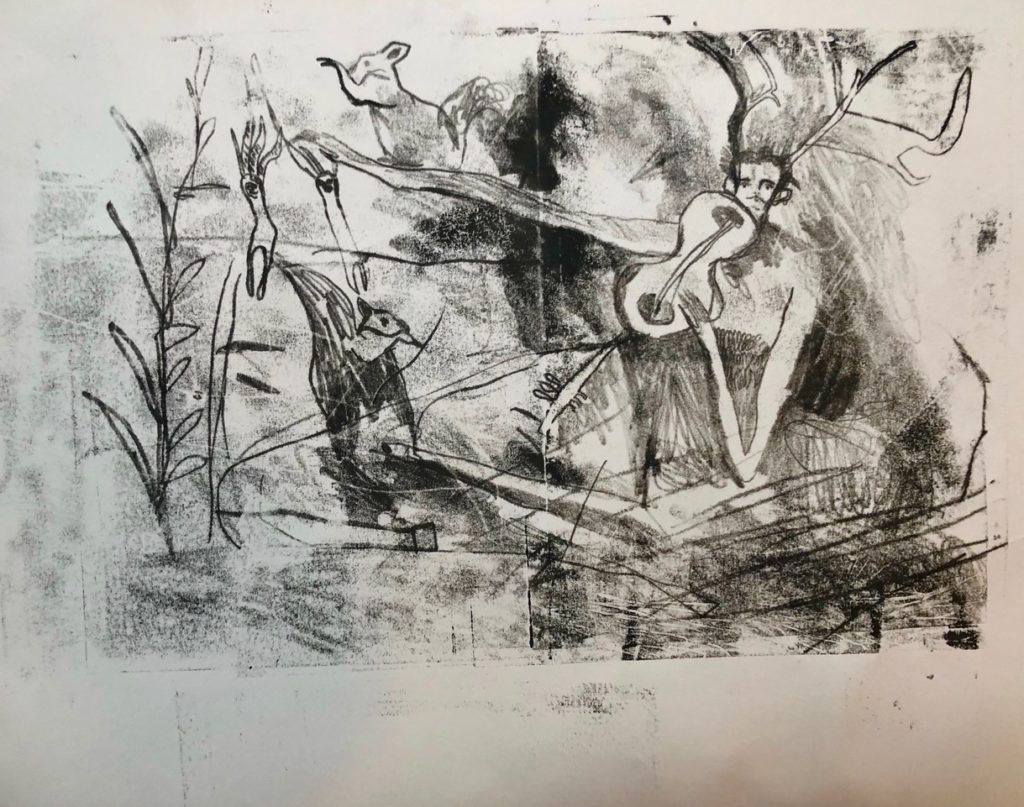

As I tried to draw an oak tree I remembered another artist mentor of sorts, a sculptor, like my uncle. He died over twenty years ago. We had been good friends in the nineties, when I was starting to draw. He had enthused and encouraged me. One afternoon he had brought me to Richmond Park to see the oak trees. He told me of the revelation he had had there one day, at a crisis point in his work, when he seemed to see all the oaks around him dancing, their lightening fork branches fizzing outwards with life. For over three years he made drawings and sculptures from the trees, they kept him company. I looked at his drawings in a book as I made my drawing for Peter Darach — the trees were like bodies. My tree seemed to grow arms, and a face appeared in the trunk, with branches like antlers — an oak spirit.

That evening, when I had finished the drawing, I walked down the hill by my house. I stopped by a tree at the bottom of the hill. It is a tall oak, with arms raised up as if in greeting. You could not hide in this one’s skirts, but her head is almost heart shaped. A plaque says that this is a Hungarian oak, planted in 1918 to celebrate the granting of votes to women. I think of it as a tall woman. Young, by oak standards. Oak trees can live a thousand years. Two thousand, according to Pliny the Elder.

My uncle once sculpted a relief of a man’s head, emerging half-formed from oak leaves. The leaves were his face and his face came out of the leaves. It was a commission, a sort of oak spirit or Green Man, and underneath was the inscription Semper Virens: Ever green, or Always living. Inscriptions or mottos were often part of his work; the one I remember most was from Shakespeare, King Lear: Ripeness is All. “Ripeness is all, Lizzie”, he said, grinning at me, exhilarated by the thought, as if it had only just hit him as he spoke it out loud, delighting in the realisation. Ripeness may be all, but just now, I would prefer Semper Virens, or “Ever living” or just, no death, no going hence — at least please not for two thousand years.

July 18th to July 25th

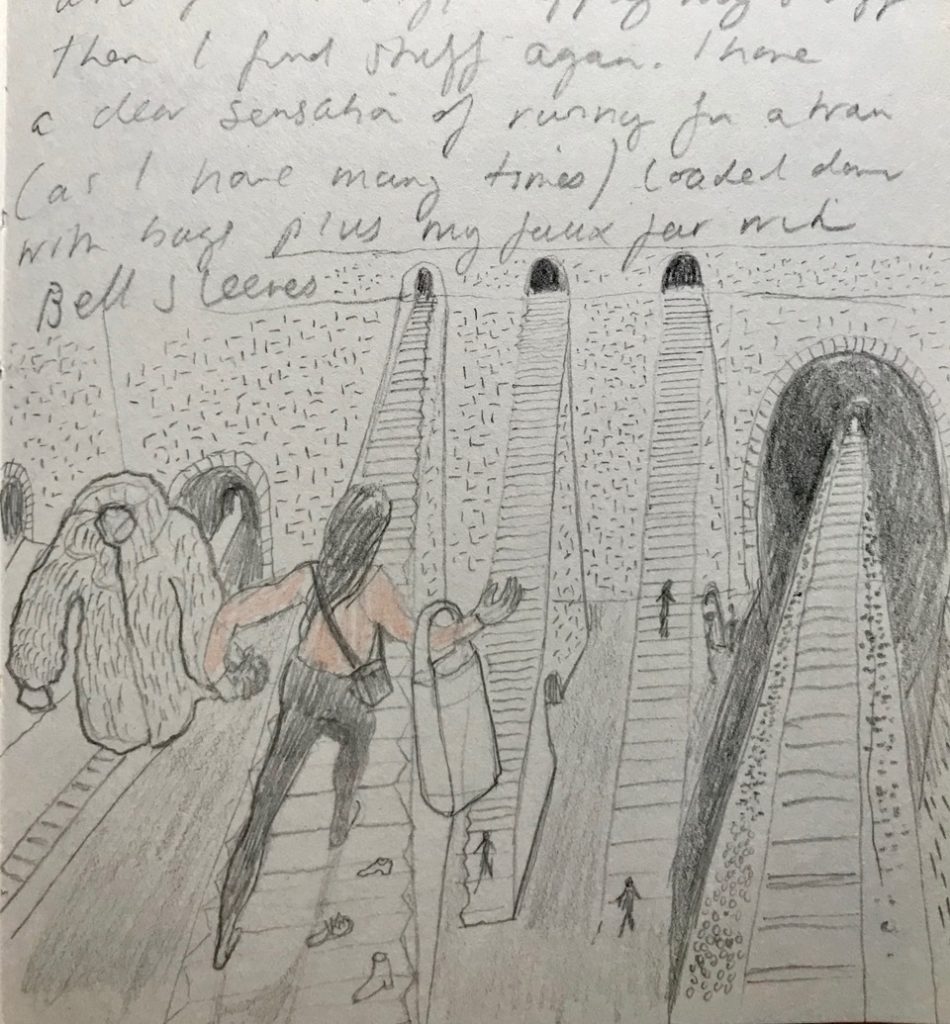

Letter from Glasgow: Train to the Future

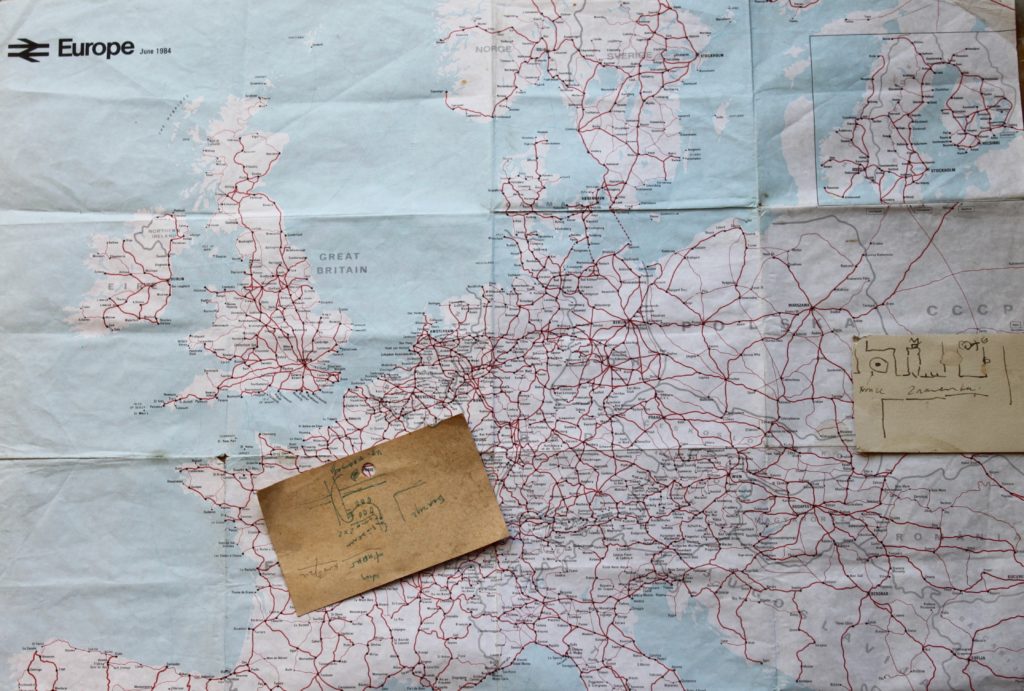

The last time I was in Prague was February 1990. I made the journey from Russia, by train. Ruth and I were part of a group of ten UK students, studying in Moscow on special visas, for ten months. We each quickly absconded from the interminable four hour grammar lessons and disappeared into different groups of artists in the city, sensing a vocation that was to prove enduring. But February was our official break from the Institute and people were eagerly heading home, planning feasts of pizza and beers in the pub after the spartan consumer restraints of late Soviet Russia. I could not face breaking the spell of this other world I had found myself in, a world in which I felt suddenly and strangely at home, among the artists, in this other language, and so I decided to take a train to Prague, as far west as felt permissible from my new centre of gravity.

The immediate spur was provided by a visitor, an older research student from my English university, M., who was also making the journey. He said why not come with me? I said why not. Sveta, the mother of my new Moscow friend, made me mustard sandwiches for the journey which she assured me were the fuel of her student escapades when she was studying at the Polygraphic Institute in the 1950s. She sat at the table slathering slabs of black Borodinsky bread with cement-like grey brown paste from jars of stinging hot mustard, produce of factory (kombinat) 61. Then my university friend turned up, dangling a white cake box on a string. Time to go, he said. And off we went.

I began to realise our differences on the train, as he sat, consulting his watch, declaring that we could eat cake at four o’ clock. I didn’t have a watch. What point a watch in the crazy mixed up time and place of Eastern Europe at the start of the nineties ? Anyhow, we were on the train, inside train time, that was relayed hourly from the radio on loudspeakers with the spooky opening chimes of the song Moscow Suburban Evenings, a familiar and slightly chilling ten note sequence, in a extra minor key, relaying “Moscow time”. So we waited, twenty to four, five to. I ate up Sveta’s mustard sandwiches. We got glasses of clear brown tea from the carriage attendant. And at precisely four pm he opened the box, with slow ceremony. But the bland piped cream was no match for Moscow’s industrial mustard.

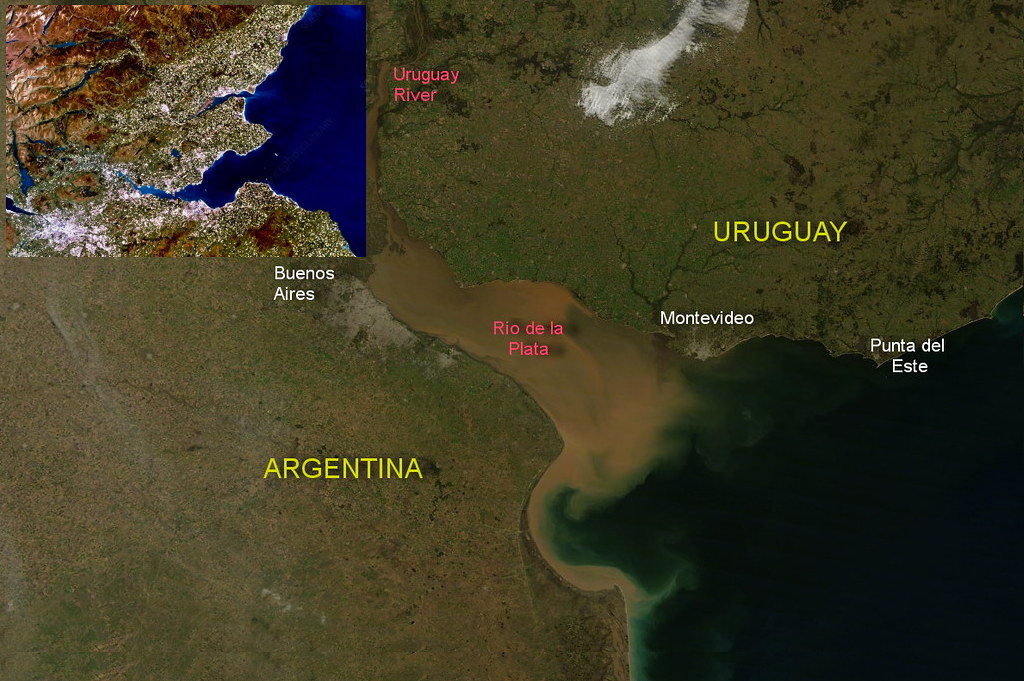

It was a slow journey, a night and a day. The train went across Ukraine. Wide fields on each side. A Ukrainian girl joined our carriage, she looked a little younger than me, she was heading to Prague to buy a wedding dress. She told us about her wedding, about the different styles of wedding dress in Ukraine and in Russia, about her plans for the future, and she wrote down her name and address on a piece of paper. Oksana. She lived in Zhytomyr. I can’t remember her surname, although I kept the paper for many years, as I have kept all scraps from such chance encounters, notes of people’s names and addresses, each in their own handwriting, like a part of them, fearing that it would obliterate something to throw them away,

The Soviet border was at Chop. We all got off the train and filed into a large crowded waiting hall. We showed passports, visas, tickets, held our faces out to receive the slow stare of the officials, and our passports to be stamped with violence. I can’t remember anything about Chop apart from the platform, the rail tracks and this large high ceilinged room, a holding room, with rows of seats and people waiting.

I enjoyed hearing about Oksana’s wedding plans, but I was wearying of my travel companion, increasingly impatient with what I perceived as his pedantry, a didacticism that seemed to hem me in. I shivered when he questioned me on what subjects I was considering studying for my final year in Oxford. Did he really think I was going back? What a ridiculous thought. England, and university finals, seemed an impossible prospect. I wanted just to stay on the train, to stay inside my new incarnation, daydreaming a future. We arrived in Prague in the evening and went out to a café to eat. I was walking along, behind M., staring at the walls of buildings, taking in their textures and only half-listening as he outlined our cultural programme for the days ahead. I sat at the meal, watching his fastidious eating, waiting until we could go. I asked for the bill, waited as he carefully checked each item and calculated my exact contribution. I went to pull out my purse and.. it wasn’t there ! I stood up began frantically looking through my rucksack. The commotion drew attention from some people in the corner of the room, then one of them came bounding towards me and locked me in a jubilant embrace. It was my old friend from Paris! He was here, with his friend, making a film. How could it be? I thought you were in Moscow, he said. Exclamations, joy, relief, and of course my friend would lend me money and of course we must spend as much time together as we could.

I was saved from cultural and worse, financial dependence on my fellow traveller. And M. trudged off to the museums alone while I rode tramcars shuttered with sunlight, my Paris friends filming the passengers as we rode to the end of the line. Prague was full of Spring — after the long dark months of the Soviet Moscow winter it was truly spring like, that February in Prague, there were lemons, and flowers for sale, and the air smelt fresh like lemons. There was cold Czech beer that seemed impossibly western, and cafés with terraces that looked like real European cafés not the windowless canteens with dirty melting snow across the floor, where you felt grateful to stand at a counter stirring a glass of muddy coffee extract, already sweetened, with a nickel spoon. Spring, or February, had never seemed so sharp and clear and alive.

There were flowers and candles on the pavements, remembering the “Velvet” revolution of the previous November. On my last day, I walked past some government buildings and saw Vaclav Havel on a back balcony waving at a delegation of nuns in the courtyard below. M. and I parted politely enough, but it was my Paris friends who saw me off. They wanted to film in the country so they decided to take the Moscow train with me, and get off before the border. They decided to get off at Olomouc. It was night, and as the train drew in we embraced and they jumped down to the platform. They waved to me as I stood behind the window, waving back. I seem to see it, my face almost indecipherable behind the dark glass, staring out under my dark cap, although I don’t think that I ever saw their film. That image, of me leaving on the train back to Moscow, is clear and distinct in my mind, as though it were me behind the camera.

I had hoped to go back to Prague for the last month’s residency, to see what remained of my memories, but it turned out that I could not. I had wanted to approach the city by train again, from the other side, thirty three years later. There would be no radio chiming the hours, no polished wooden corridors or jars of tea in metal holders, perhaps no mystery. A journey of nostalgia, of curiosity? Certainly not the journey of my twenty one year old self, whose trace or ghost lies somewhere on frames of celluloid, heading back East to a still unthawed Moscow, full of resolve, to meet the unknown future.

July 11th to July 18th

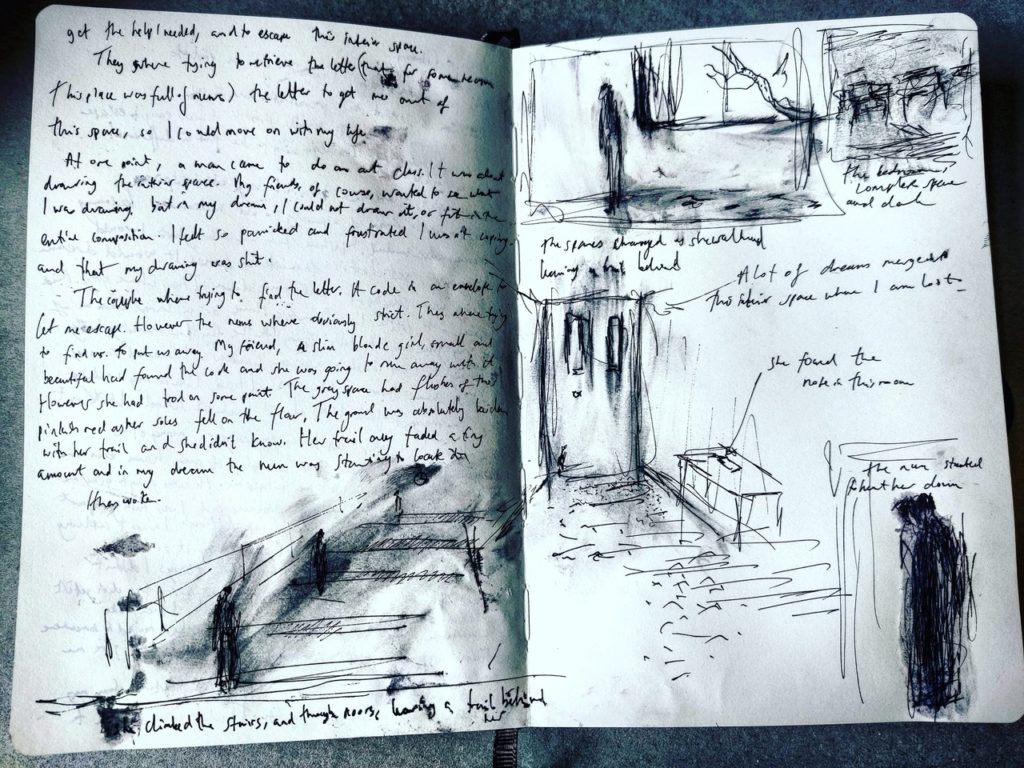

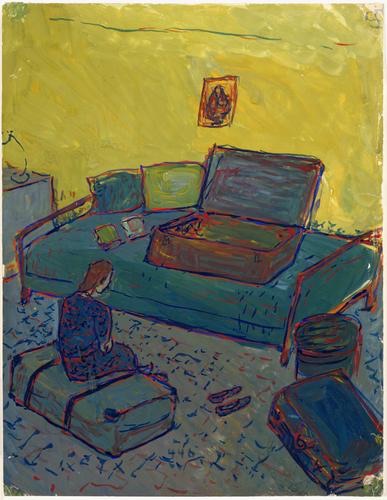

Letter from Glasgow: Drawing and Losing

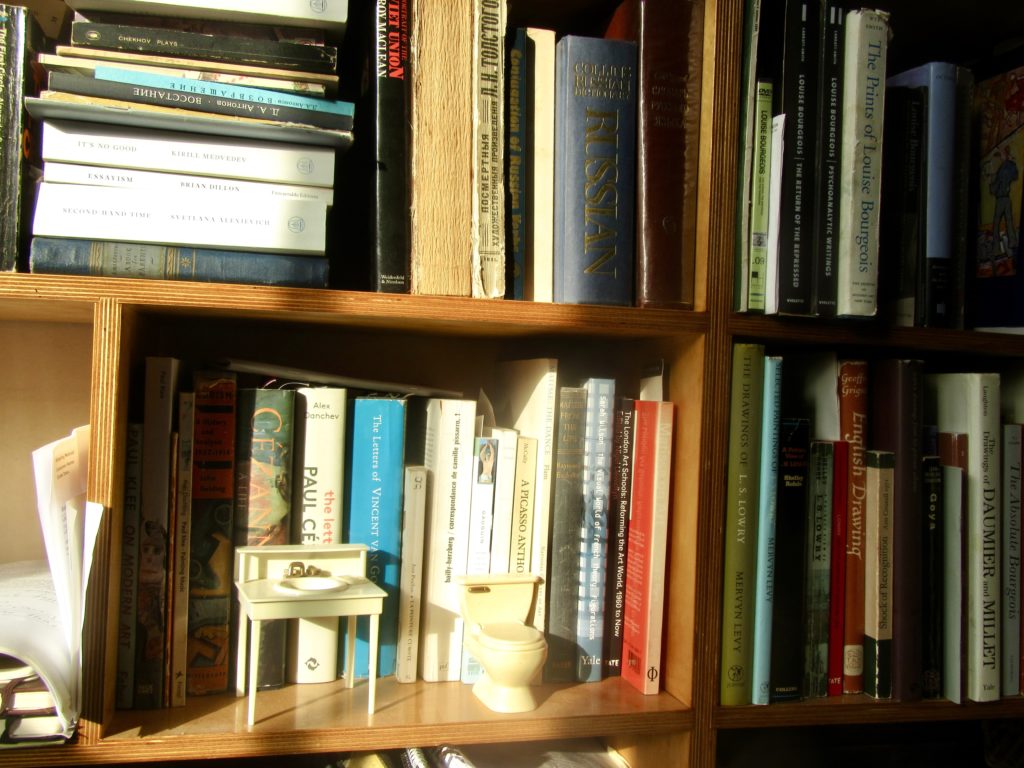

It is end of term at the Drawing School where I teach. My children are away and I am alone in the house. It should be the chance for the solitary work I have wanted all year, but I am exhausted. The first two days I lie on the slightly uncomfortable but very Freudian couch in the corner of my room, staring at my bookshelves. I acquired the couch last month, a friend was getting rid of it. I had assumed that it originally belonged to his mother, a psychoanalyst, after all it used to sit in his flat under a shelf of her complete first edition of Freud in English, that he inherited when she died. But I was wrong, my friend said. The couch, that I had always imagined to be saturated with residues of dream narrations, had in fact a sadder tale. It had belonged to a university friend who killed himself, and bequeathed the couch to my friend. Only it turned out that my friend’s friend had had a completely different name, to the astonishment of his contemporaries. They had never really known him. He said that it was a relief in a way, to give the couch up.

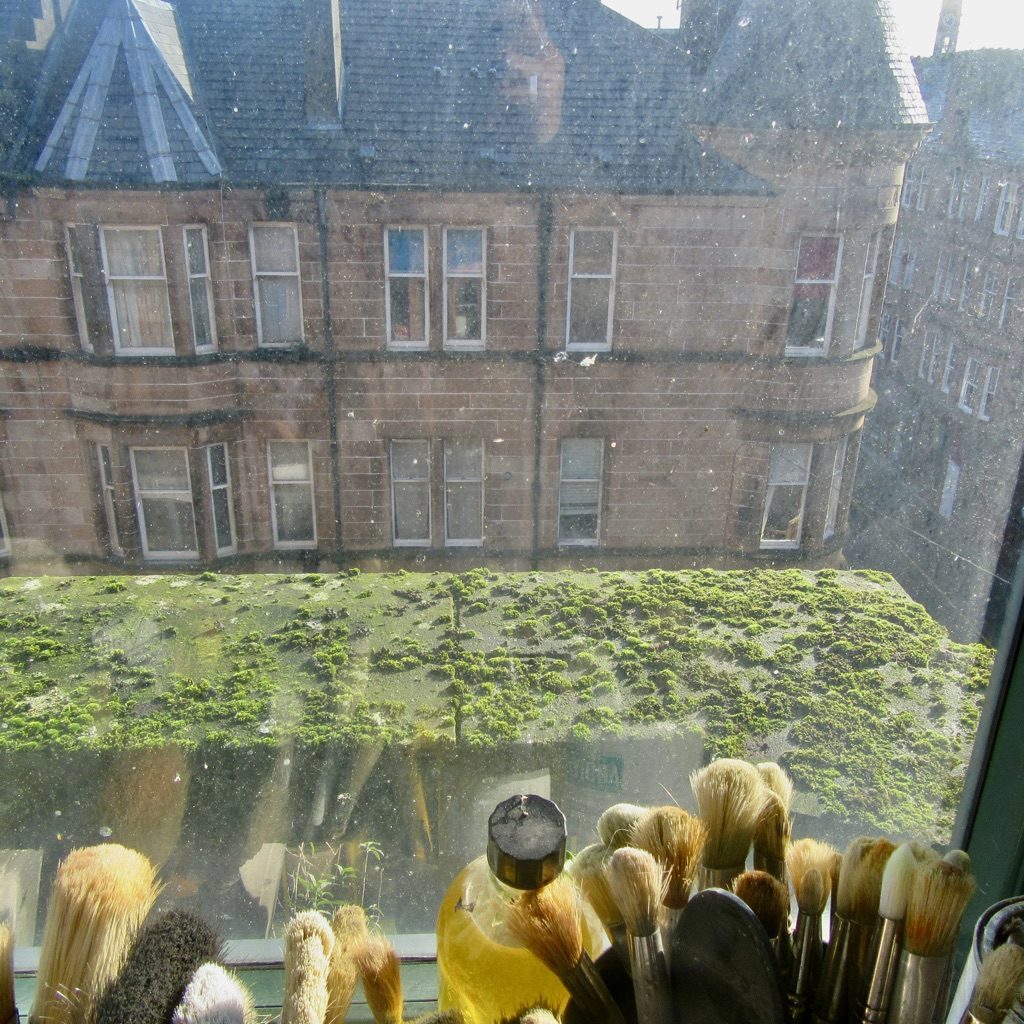

I covered the couch with a Qashqai rug, a worn runner that my mother no longer wanted, but which was too long for my hallway. It fitted just right. I added some cushions and a blanket. It made a pretty good near relative of the couch in London, at the Freud Museum. It was somewhat creaky, being over a hundred years old, and had un-sprung itself in places, but I like to lie there and stare, out of the window, along my bookshelves, daydreaming.

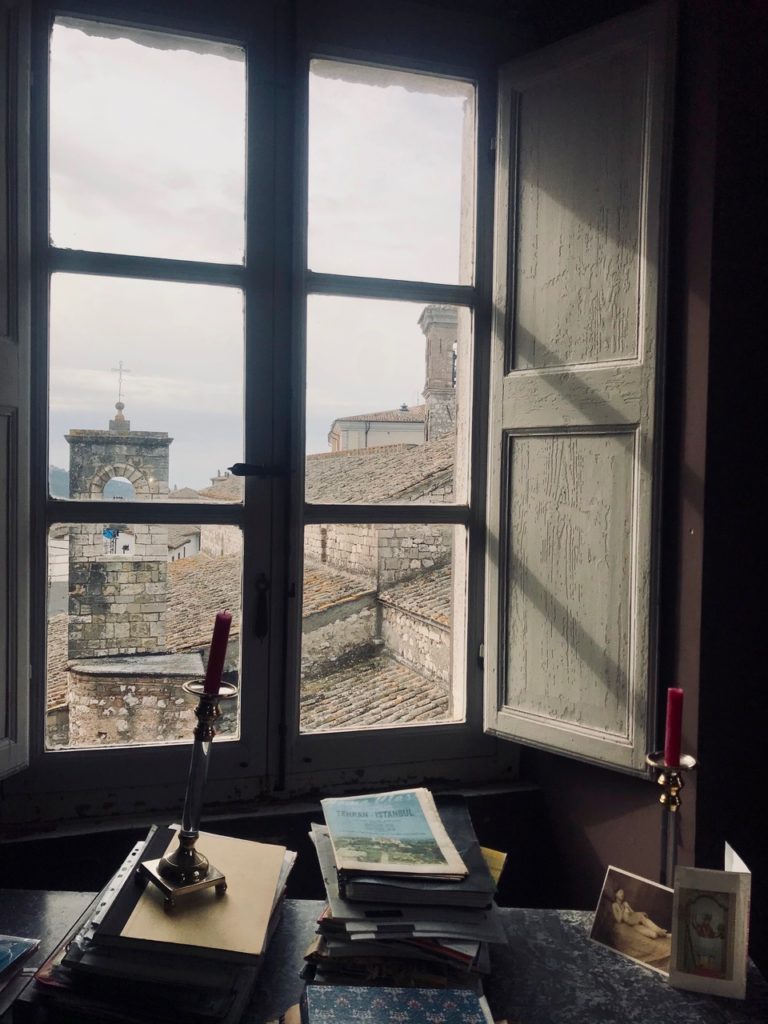

On the third day I began to grapple with the piles of paper on the shelves at the end of the couch. I sat on it and sorted old drafts into some sort of pattern. Notes on drawing, lost and forgotten drawings and writing — they disappear and re-surface, always I am trying to find some better way of putting them in order, of finding what I need.

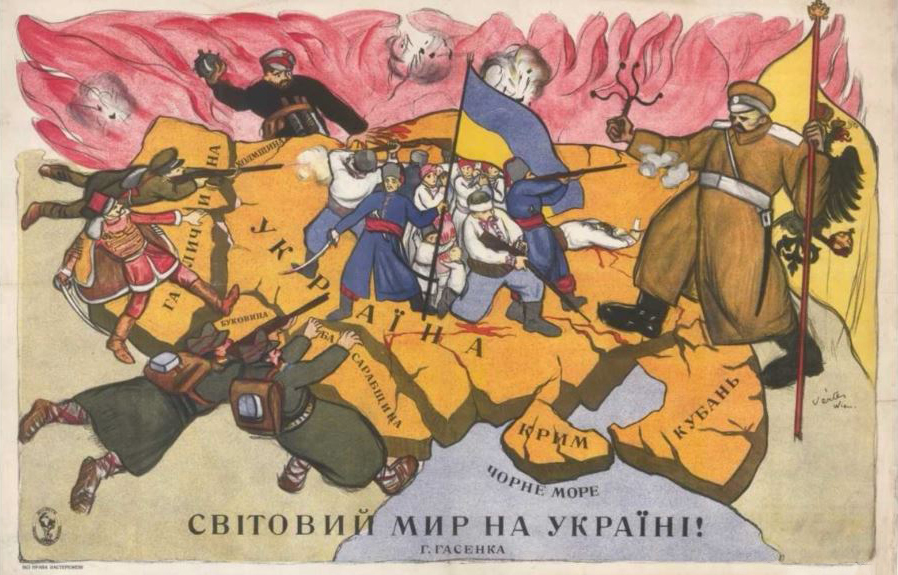

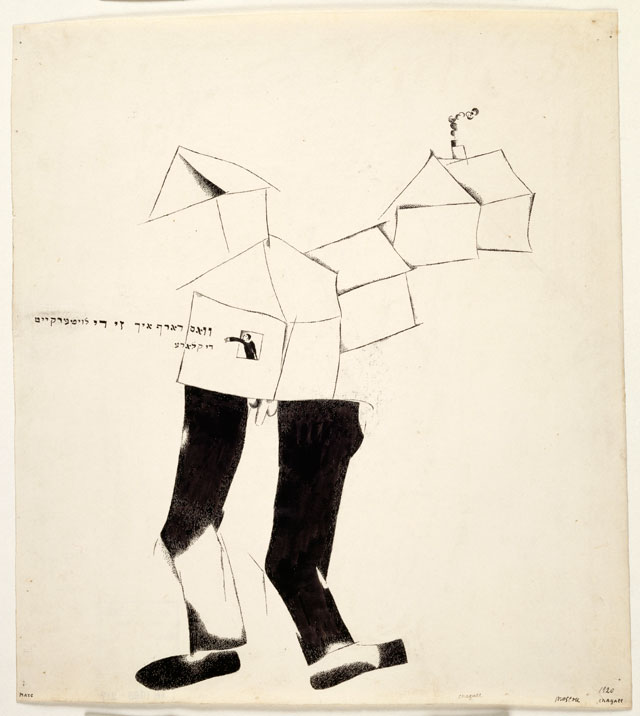

As I sorted and re-arranged, a quote from Chagall surfaced, that I had copied out several years ago. He is writing about the one million Jews forced from their homes on Russia’s western front in 1914, through a combination of state ordered deportations, local pogroms and massacres. Chagall wrote of these figures without homes, walking east: I longed to put them down on my canvases, to get them out of harm’s way. It happened again all too soon, with the terrible pogroms of 1919 that took place in Ukraine during the civil war. This time Chagall made a drawing that shows a raft of rooftops, a whole town, being carried on a man’s naked legs. The Town Walking (sometimes called The Village Walking) was drawn in black ink, in 1922, to illustrate a Yiddish poem of lament for these atrocities, Troyer (Grief). The poem-pamphlets were sold to raise money for orphans of the pogroms, who Chagall taught drawing to. A figure looking out of the window of the house on legs emits a scroll of Yiddish letters, a speech bubble: What Use to Me the lucidity, the clarity ? I had thought about this drawing at the start of the war last year, as people were displaced once again, the towns walking across Ukraine a hundred years later.

To get them out of harm’s way. Chagall’s wishful intent reminded me of Sudha Padmaja Francis’ last Crown letter from India, showing the drawings she had made of her friends. She wrote that she isn’t interested in fluency or strong lines, but that her drawings are a way of keeping company with friends, often absent, a way to bear witness to them, perhaps hold them, when she is unable to actually reach them physically. Drawing as a way of protecting.

I have never met Sudha but the warmth of the writings, films and drawings she sends to the Crown Letter makes me feel that I have been inside her family courtyard, with the fallen mango leaves on the ground. It feels like a protective space. I think about about Sudha, about Chagall, about drawings made as a way of bearing witness, a charm against loss. Like the old myth of drawing’s origin, which features a woman, a sculptor’s daughter, drawing a line in charcoal around the shadow of her lover before he leaves her for a long journey, a way of holding a trace of that which is about to vanish. I am glad that Pliny the Elder records that this initial impulse came from a woman, the only female creator he acknowledges in his Natural History. Although her work was completed by the father, who made her drawn image into a clay relief, it was she who had the instinct to catch the shadow of a loved person with a drawn mark.

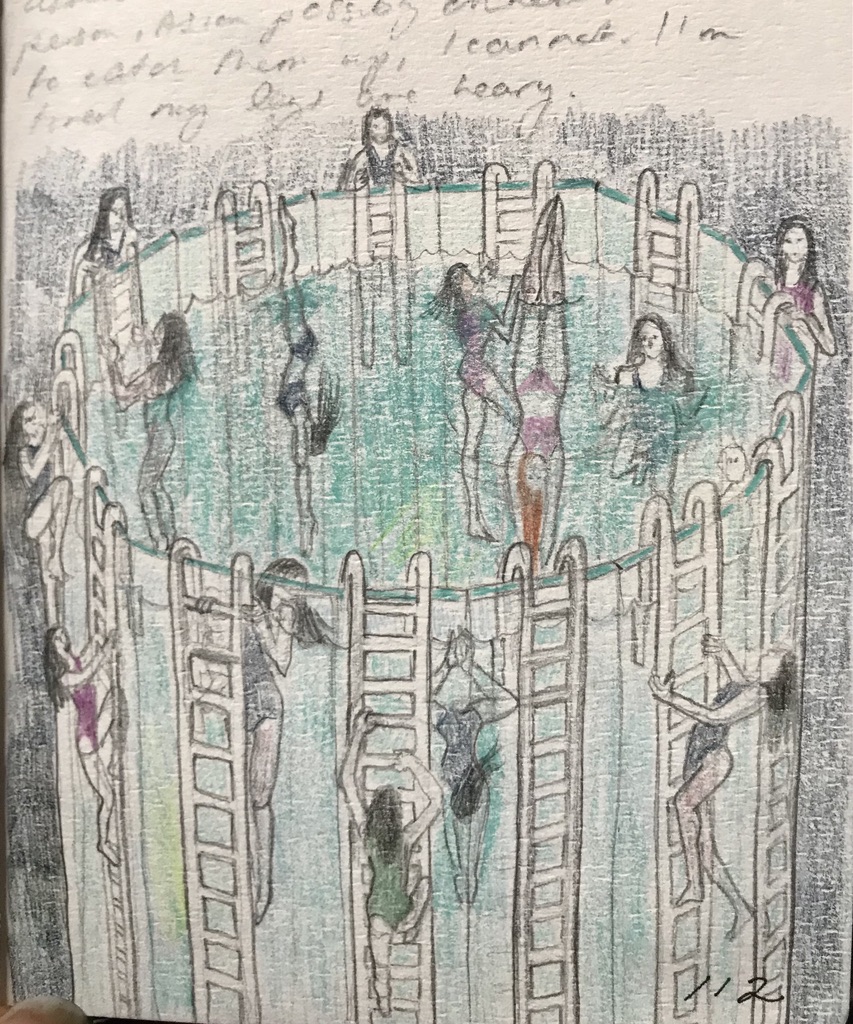

What use to me the clarity, the lucidity? Classification continues to elude me, and the re-arranged papers form a new pattern on the carpet covered couch, in this endless circle of losing and finding. I wait there, to see what might emerge from the shadow traces, in the daydreams, resisting a definite outline, remembering friends, dreaming of ones I cannot reach, of places that cannot be got to, the places in dreams, that hold the best of what we can be together.

June 27th to July 4th

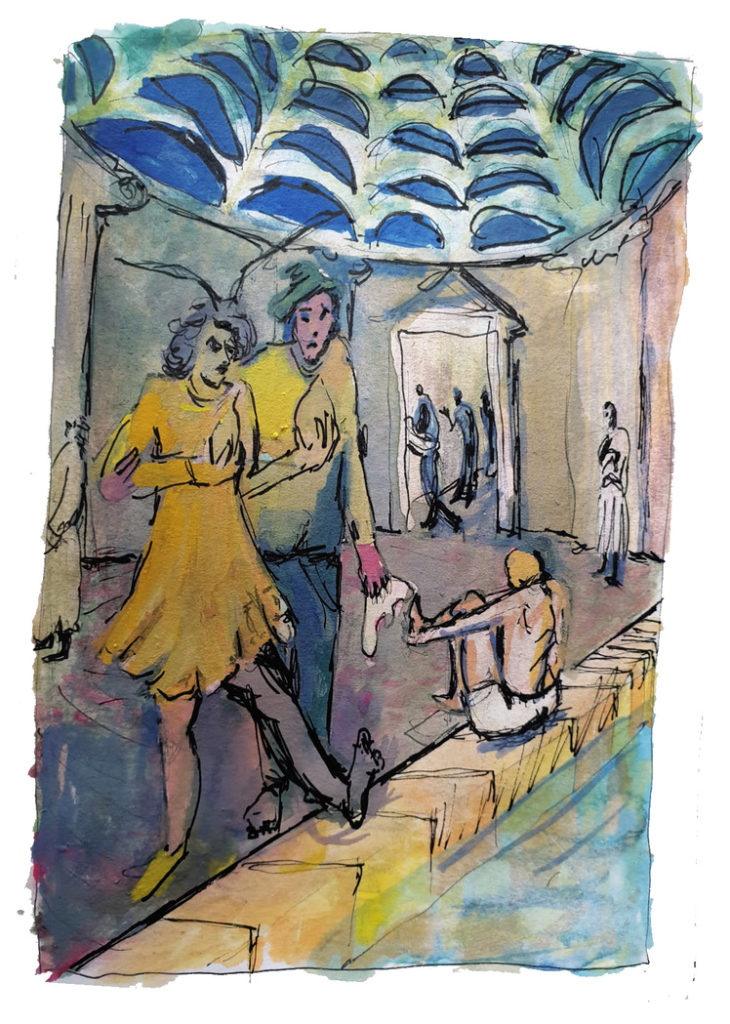

Letter from Glasgow: Looking to Sea

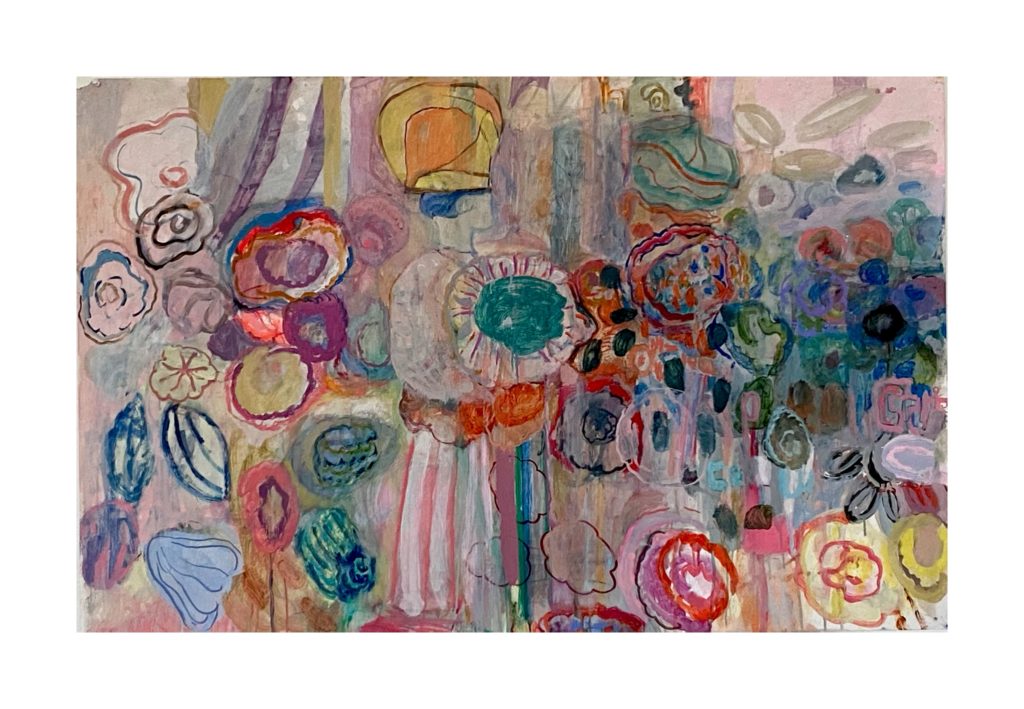

Last weekend we went east, to the capital, for the exhibition of a friend’s paintings. It was a morning opening. The sun came in to the large square room through a domed glass roof, the tracery dappling light on the surfaces. The canvases were large and square, you could swim about in them. One was an underwater picture, a mosaic floor with the shadow of goldfish across the tiles, a suggestion of fish. The room was full of watery light.The paintings were inflected by the light and the light by the paintings. The paintings were so big you could be inside a painting and among the people in the room at the same time.

Afterwards we went swimming. The city is on a curve, lapped by the north sea, so the streets go down to meet the beach. The beach was full after days of hot weather, although the sky was now overcast. There were many of us. Mostly painters, we had shared the same studios in Glasgow for twenty years or more. We had seen each other through break ups and births, deaths, and threats of death. Most of us were still painting when life allowed it. Our friend had become quite famous, but we were glad for him. His painting made you want to paint.

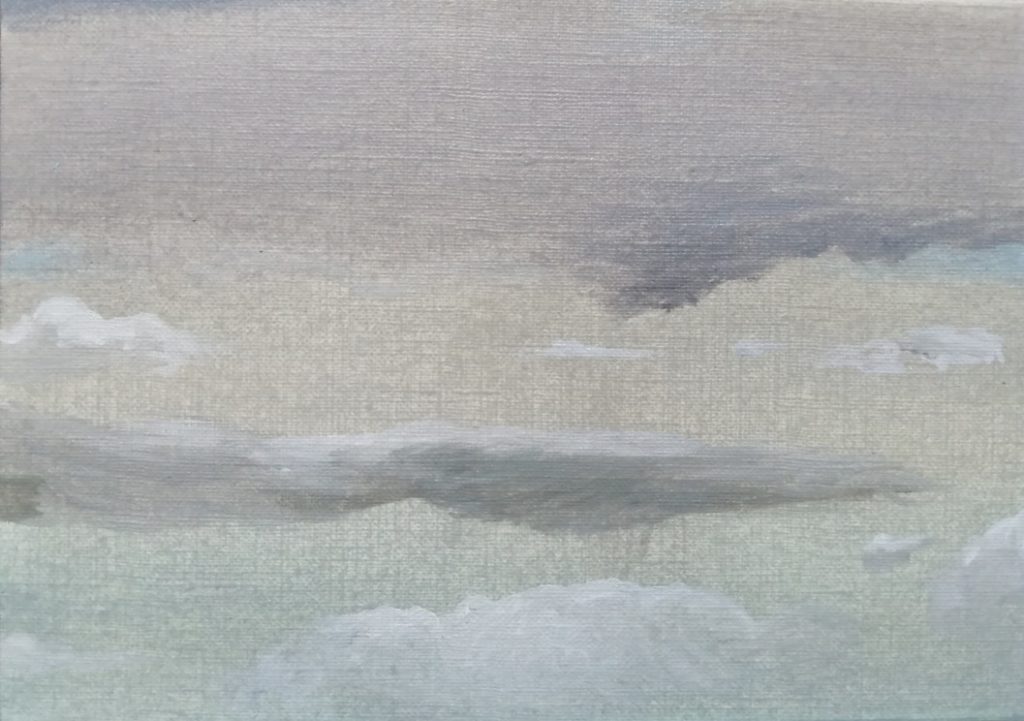

We walked to the water’s edge where a line of dead seagulls, some of them picked to the bone, were washed up on the tide. It was said that the North Sea was five degrees warmer than usual. Last week a humpback whale was seen in the Clyde. The sky was dense as before a storm. The browny light of it reflected in the cloudy brown of the sea, or was it the other way round?

I swam out, leaving my friend paddling on the shore with her young daughter. It had been some time since we had all been gathered together like this, with children, in a holiday mood. The teenage boys were now taller than their fathers, and looking from this distance, their fathers were suddenly more frail, scanty haired, and the boys were men. We had all grown older. I swam out for a while, backwards, watching my friends on the shore and their children becoing smaller as I swam further, and then I turned around, and swam back in, keeping my eyes on the empty horizon across the warm brown sea.

June 20th to June 27th

Letter from Glasgow: Instructions for a Heatwave

It is a heatwave, almost midsummer. I’m at the Tramway art centre on the south side of the city, to hear my daughter play music at the opening of an exhibition of children’s art. I’m early but I can hear the sounds of strings, so go up to the roof space where they are practicing. They are playing in front of an arched window and through the window there is the distant outline of the Campsie hills beyond the city, almost dissolving in the blurry haze of heat. This was the same view that I saw, in another heatwave, in the summer of 1994, when I first came to Glasgow. There was a performance of Dostoevsky’s Devils by the Maly theatre, on tour from Moscow. My friend was translating for the company. I booked a train.

The play was performed over a day, in three sections, with substantial breaks in between to eat and draw breath. The audience sat out in a line, seeking shade under the awning at the back of the building, that was still being converted from the original tram depot. We stared into the heat, sipped water and ate snacks. On the second break I went out of the building, in search of a samosa, and a pencil, from the local shops. I crossed the railway bridge and looked out, my gaze held suddenly by the line of hills beyond the city in the soft evening light. From the bridge I could see the city, the high flats and the university towers and beyond them, the now familiar outline of hills.

I thought, I could live here. I walked on to a small newsagent further up the street and imagined myself to be walking in my own city. A sort of premonition. The next day, waiting to board my train back to London at Glasgow Central, I drew the tented glass-paned roof of the station and knew that I would be back. It was as though I recognised something about the station, or the view from the railway bridge, as if it had managed to inhabit me already — my future held within me. My future at my back as the Tuvan saying has it.

But it shocked me to realise it — that future, now present, and suddenly overlain by the first sighting of it almost thirty years ago, to realise how I had taken my premonition at its word. How stubbornly I had persisted with this city, following that early summons, in spite of disappointment, a love affair and its demise, a future that felt unfathomable. I had stuck with the city and gave birth to two children here, and now here was the youngest, my teenage daughter, dressed in black, playing a violin — a silhouetted figure against the exact view that I had felt the future in, as close as that, with almost no space for all the labour in between.

After the music, my daughter came up to me. She said, I saw you looking sad. Was I ? I asked, I was just looking.

In the enormous downstairs space the concrete floor is grooved with shiny curving tramlines. There is a show of sculpture by an artist from a Sikh family, she was born a few streets away from the gallery in 1986, a child when I first came to this space and walked through Christian Boltanski’s Lost Property exhibition, in one of the breaks in the Russian play. The gallery attendant has left the room, a clipboard with her list of visitor numbers lies on her chair, and a book, Instructions for a Heatwave. It looks like a novel, not a handbook. Although we could do with both. The heatwave is much hotter than the one thirty years ago. It is still swelling when my daughter and I leave the building at ten to six. We cross the railway bridge and walk along the pavement, keeping inside the shade. A little further down we see boxes of new season mangoes piled up on a makeshift stall in the street. The stall stands almost exactly at the spot where I had bought the pencil, samosa and small red paper notebook that early evening almost thirty years ago. It’s a short season I say, we should get some. By the time I have paid a small queue of people has formed behind us, trailing back into the road, men in turbans and women in glittering cloth. We walk along the street balancing mangoes, violin, and a heavy school bag. The buildings are almost whited out, over-exposed, the sandstone that looks gentle against a storm sky is suddenly insistent, it hurts the eyes, the light is too bright.

Instructions for a heatwave ?

Walk more slowly. Don’t look back.

June 13th to June 20th

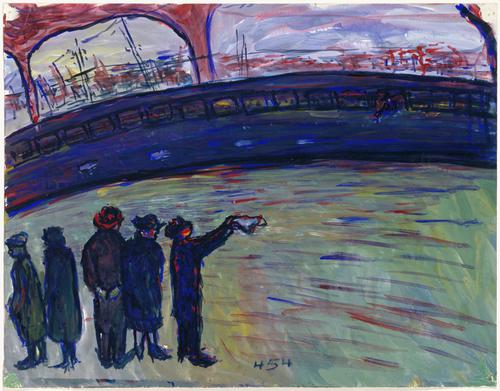

Letter from Berlin: Ghosts

We were late for the film and the box office had just closed. They said we could have a drink instead. And so we ascended the stairs into the wide space of the bar of Kino International, which was completely empty. A small person appeared at the counter and poured us glasses of Riesling. The great glass windows held the deserted streets of old East Germany, looking more than ever like the past on this Whitsun weekend. Opposite was the MOSKVA café and cultural centre. My friend said it was closed at the moment. The writing on the building and the wide empty street reminded me of the road of Moscow’s New Arbat, that I would cross and re-cross several times a day whenever I visited, as my closest friends lived on each side of it. On some visits the walk between their two kitchen tables was all I would do. I know the wobbly line of streets that join them in every weather and at every time of day.

Kino International was built in 1961, the same year as the Berlin Wall. It was the main cinema for premieres and award ceremonies under Communism. You could picture it, the slightly sweaty dignitaries in brown suits and shoes of turgid grey fake leather lined up for speeches under the extravagant chandeliers. But this evening there was nobody. The huge yet undaunting space, the rippled wood walls, shiny black tables and red chairs were perfect. This enormous empty room was proportioned for optimism, it was a place to be happily human, for a while at least. I was glad we had missed the film. I looked across the street to the high Soviet scale arch of a metro exit, the only lit building on the street, and watched a couple pause, pace about, embrace. They were tiny under the space of the arch and yet every small gesture was legible.

That afternoon we had cycled to the far west of the city, we had stopped at a flea market, or rather I leapt from my bike, spotting a pile of old photograph albums on a table next to the cycle lane. A box under the table held postcards, letters, photographs. There were letters from Russia with the imperial eagle on them, sent before the revolution, and letters in German, from wartime, dated 1942, and then from the divided post war country, written in ink or whispery pencil. Photographs of groups of young people, smiling in mountain landscapes, or wearing swimming costumes at seaside resorts, from the 1930s, full of Aryan health. What did they know, what were they thinking about? I thought about the Russians writing letters to Germany, about the endless configurations of families and the handwritten news travelling to and fro. We stayed for ages, I needed to go through every envelope and every image, as if I was looking for something.

Occasionally, the strong face of a young woman looked out, distinct, thoughtful, a lone portrait between the robust groups. I wondered what she was reading, who she wanted to be. I was tempted to ask if I could buy one of these photographs, but I did not want to separate them from their company. Also, what if someone else was looking for them? Someone who they belonged to. Even the letters in Russian, that I could read, were not addressed to me, and might yet be awaiting their rightful recipient. The men running the stall seemed uninterested in what they had, the envelopes, photos and albums were piled up in a careless heap, they were doing a brisker trade in a pile of shiny modern ceramics. I straightened the albums into some sort of order. I put back the pages that were crumpled or falling out. I felt it was my duty to look at every bit of handwriting, each photograph, just in case, but I did not feel I could buy any. They were not for me to take, however beguiling the faces, intriguing the handwritten pages.

When I lived in Moscow, I used to go with my friends to the “Cinema of the Repeated Film”, near their flat. It showed old films, Soviet and a few European ones. In the autumn of 1989, as the Berlin Wall came down, we went to almost every screening at a festival of Soviet silent movies: Boris Barnet, Dovzhenko and Abram Room. The faces were compelling — a sudden lit proof of real people and rooms in a real and urgent time, that had since become history. Like the faces in the albums, in the boxes, they are so many. They look back at us as we move forwards into the past. What should we do with them, with these shadows, these flickering urgent ghosts?

May 30th to June 6th

May 23rd to May 30th

Letter from Glasgow: Written on birch

The first letter my father sent me was written on birch bark, paper thin, in black ink. He posted it from America, or Canada, where he was away working. I was too young to read it, only two or three, but my mother must have read it to me, and she put it in her scrapbook where it remains intact.

Every week I walk through a tunnel of birch, the long trunks seem to have eyes, mouths and other orifices. They look back at me, and I mark my journey by them, the big staring eye, the shape like a gaping vulva, a sheela na gig. The trees feel alive, watchful, warding off trouble. In spring their high thin leaves dapple the light and enclose me.

Birch trees seem to like railways, you travel through them as you enter Glasgow, and Berlin and then east to Moscow and Siberia. An endless shuttering of birch trunks through the train window, their verticals marking the space. It isn’t monotonous, it is even reassuring. They accompany my journeys, anticipated and remembered. I look them in the eye.

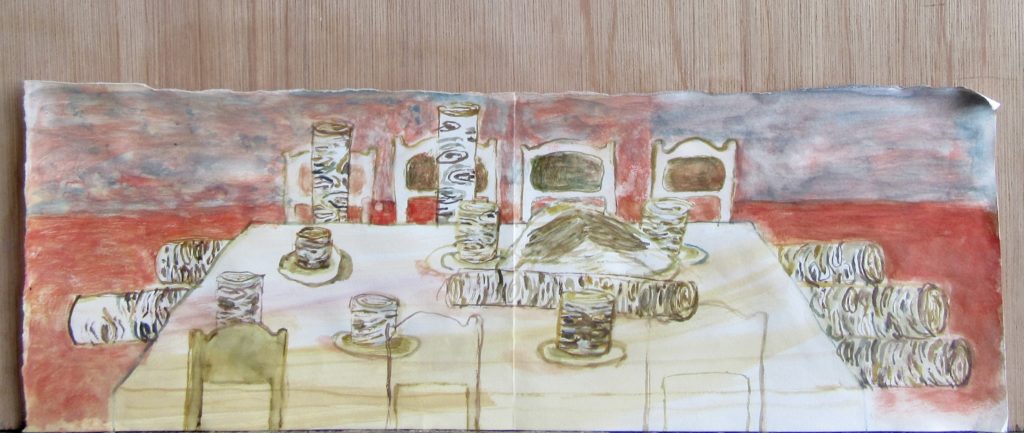

Recently these tree trunks have begun to people my paintings and drawing. They sit about a dining table. A felled tree between them like a family secret, or a dead man laid out. What do they do with something that is part of them? The trees are cut at different heights and sit at seats or on plates. Some places are empty. Generations of birch, you could find the continuity consoling. I find it frightening, such inescapable belonging.

May 16th to May 23rd

Letter from Glasgow: A bed of lichen, a table of moss.

This morning I was woken by a text from Paris. My old friend Anna-Louise is making a headdress to wear to a carnival this afternoon, planned by the locals of her area, with and without papers, who she has worked alongside for many years making breakfasts, music, and street parties for those forced to inhabit make-shift camps that surface and are just as swiftly cleared on spaces of land between the expensive square metres of the once shabby 18th arrondissement, where she lives.

It’s going to be a Bibiliotheque Imaginaire, she writes, an imaginary library, to wear on her head. Can you send me the title of a book, real or imagined? The first thing that surfaces is moss. My book would be a bed of moss, but I need another syllable. A mattress of moss? No, a mattress feels too awkward and practical, a table then. She likes it. A Table of Moss and Other Stories? Yes, it might include Un Lit de Lichen, I text back.. Something solid and permanent like moss, or lichen. But my predictive text wants to write libido, not lichen. Although it is true my devotion to lichen might have something libidinous in it. And I have long dreamed of beds of lichen and moss, and sometimes trees are asleep in these beds.

As I was day-dreaming titles I had not been thinking of the camps or of the actual, not mossy, but decidedly urban mattresses that are left behind after each clearance, the one thing that people cannot run away with. The mattresses are always the first things to be brought, dragged over pavements, and the things that remain after everyone has been moved on. The beds of moss, or lichen, indicate a world where it is safe to lie down anywhere, where nobody claims possession of the territory and where you can gently dream. A sort of permanence, old as lichen, as libido.

May 9th to May 16th

Letter from Glasgow: Notice of Death

How do you spell bereavement? My friend asks. I’m sitting in my kitchen spelling the letters out loud down the phone: B_E_R_E_A .. and then I pause, for I can’t remember if there is another ‘e’ after the V. My friend’s father had died in his sleep, but still it was sudden. I saw the text when I woke up. I rang him as soon as my daughter left for school. He had already made it home. His mother asked him to make a sign to put up in the window of the shop. She is in her late eighties but still runs a busy dressmaking and alteration business in the local town.

How many Es in bereavement? I think I was one short. But I hoped it wouldn’t matter. Closed due to a Bereav(e)ment. “Closed until further notice due to a bereavement..” that was the sign we saw in the window of a garage in Orkney, where we had been hoping to buy some food. It’s possible it was also misspelt. The sign was so old and faded it looked like no-one had ever come back. The bereavement was interminable. The crisps we had hoped for and the packets of tea going out of date on the shelves, the petrol pumps rusted and faded. We walked to the nearby bus shelter and stood there for an hour out of the gale, waiting for a bus.

How many Es in Bereavement? The spell check on my computer keeps adding in an extra e when I type it, so I think I told him wrong. There had seemed something absurd, yesterday morning, ringing my friend to condole him and sitting there spelling out B_E_R_E_A, spelling out the facts of the matter, and the spelling being the only thing I could help with at that distance, and still I got it wrong. And he would have trusted me as well, to spell it right, me having an academic education and two university degrees. I usually can spell, but I left out the E. It felt like there were too many. I made it more abrupt.

People wouldn’t mind, they almost expect mistakes. There is something so abject about those handwritten signs, put up in haste and the door shut indefinitely. “Maybe he got out by the side door.. ”, my friend had said about his dad. I had to pause to take in what he meant. He meant, I suppose, that his father, who had recently been diagnosed with a horrible neurological condition, had died peacefully, without even waking his wife, who slept beside him, and so had avoided a more torturous end. My friend had also said, about the grief, “maybe it’s in the post”. I wondered what, but he meant that he still felt numb, he was waiting. Death had been expected, but it had arrived early.

“I didn’t draw him” he said. I said it didn’t matter, he had drawn such beautiful portraits of his father when alive. “I thought it would be disrespectful”, he said. “And they are taking the body away now..” As if he slightly regretted it. He said that maybe he would draw something from memory. That had been the name of the book of prints he had made, images of his family, he had bound them in a hand-made book. Io ricordo was the title printed on the front, in the language of his parents. And then we finish composing the sign. “Completed alterations can be collected from Giovanna, at the Florist next door.” That seemed enough. Then he had to go, to put it up before opening time.

May 2nd to May 9th

Letter from Glasgow: Shadow Boxing

Last week in London, spring was fizzing through branches of willow and lime, leaves unfurling in brightest yellow-green. I got off the train at Kings Cross and took a bus up the hill to Angel, through the blossom and the new leaves. I met my aunt at the top of the hill and she led me to a pub with a high-ceilinged back room, out beyond the bar and the noise, where we could talk. Sunlight striped the dark wood floor and the almost empty space was a relief.

My aunt bought us drinks and we sat at a table in the corner. She sat beneath the window, a dark figure against the sun, but light fell also from a smaller window at the opposite diagonal of the room. We were talking about death and of people close to us who found themselves suddenly in its shadow. My aunt was speaking and as she spoke I watched the clear shadow across her — the great bowl shape of her glass and the straight straw coming out of it, enlarged on the front of her tunic, cutting a fine silhouette against the white-green brightness of the sunlight. The shadow focused the brightness of the light, this new spring brightness, or the light focused the shadow. I watched the way that its edges hardened and relaxed, sharp and then soft. I took it inside me, as I took in the sad drudgery in her words, as we circled the inescapable. The shadow was a surprise — the April light so clear and precise, the shape made by it so unexpected. I held onto it like a rope that you grasp when the space ahead is uncertain or treacherous. That strong and playful shape was a gift and comfort, as was the looking, a more hopeful conjuring than the words with which we tried to muffle our dread.

A week earlier I sat with Ruth in the old stone church at Dunnet on the edge of Scotland, on Easter morning. Ruth had been married in this Church. I sat, like a child, between her and her husband. The visiting preacher asked us to imagine Jesus walking down the aisle in a blaze of glory but we were concentrating on the shadows behind the blinds on each side of her head. The shadows were moths, caught between the blinds and the long coloured glass windows in the side wall.

The glass in the windows was pale pink and a warm yellow. Their gentle warmth made a pleasing contrast to the more austere dark red and blues that are usual in church glass. There was no lead tracery, simply ordinary panes of coloured glass, slightly rippled as might be found in a school or nursery. The colour was like blancmange or custard, a nursery pudding or a children’s book. Something simple and benign, reminding of school halls, of childhood spaces. They were soothing. On three of these windows the blinds were drawn shut against the sun, but the light through the blind was tinted by the coloured glass.

The sun had just come out and drew a silhouette of the moths between the glass and blind, a shadow shape that sharpened and blurred with the stir of the breeze, their edges lost then found, as they flitted against the glass. I no longer regretted the sermon, nor not being outside in the sunlight, I was with the moths and the blinds that twitched and shifted slightly in the wind, focusing and dissolving with the light and air.

I thought of Ruth’s drawing of moths in a recent Crown Letter and of Virginia Woolf’s fondness for moths, a motif in her work for flashes of imagination and intuition. The Moths was Virginia Woolf’s original title for the book that became The Waves:

The contrasts might be something of this sort: she might talk, or think, about the age of the earth: the death of humanity: then moths keep on coming. (Virginia Woolf’s Diary, Saturday 18th June, 1927)

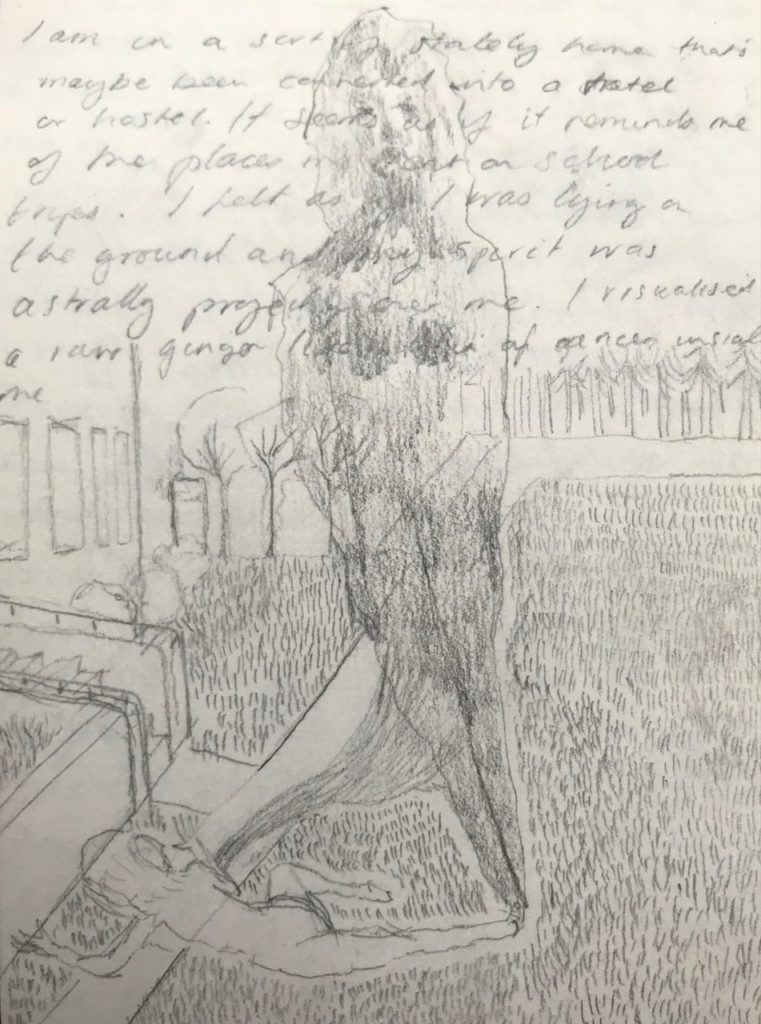

The waves crashed below us. The church was an unusual shape, the pews set in three directions to form a T. Ruth told me about her wedding and about walking in down a side aisle and seeing her uncle and her brothers sitting facing towards her, all of them crying, even the one who never cried. I could picture Ruth entering the church and drawing tears far more easily than I could Jesus. The service ended. We went out into the light. We walked through the graveyard at the top of the cliff. We looked at the headstones and the carved names, archaic and familiar, at the crispy bright lichen on the stone. One grave had fallen and broken on the ground. I thought of a dream I had had about dying — people were moving through a landscape but as they vanished, or were claimed by death, their shadows stayed behind, they kept moving, darting over the empty ground. The shadows held the specific trace of the vanished person, these markings on light became their permanence.

I had been surprised by the dream at the time and I still wasn’t sure what it meant. It was something to do with wanting to hold fast to life, a longing for permanence — but knowing that permanence cannot be set in stone. Sepulchres and monuments do not return a person from death, but perhaps, if we concentrate, we might sense their shadow. Shadows seem so calmly articulate, their movement compels because they seem to be saying, or showing us something, patterning the pile-up of objects through which we stumble each day. We can follow their movement when we don’t know where to look, or which way to turn.

Perhaps they are showing us a way to give up our fixation with monuments, our need to counter loss with solid objects, reminding us that nothing can be caught or held, but that shadows are a sort of constancy. They comfort with their ebb and swell, the soft valve of their play like a promise, a stilling, a way to be carried, or at least a way to wrong-foot our fear.

April 25th to May 2nd

Letter from Glasgow: April around the tables

April. It was Passover, it was Easter. Then it was Orthodox Easter.

We spent Passover week travelling, setting out on the first day and taking the long train north through Scotland, from Glasgow to Inverness and on to Thurso, the furthest point of the Scottish mainland. I had been invited to a seder but had had to say no as we would be travelling. I was curious as I have never been to a seder, although a friend once shared with me the hard boiled eggs in salt water and bitter herbs, one April in the Hebrides.

In Caithness on the north-eastern edge of Scotland we feasted each day of the Easter weekend on roast meats and puddings, cooked by my friend’s mother. The long oak dining table was laid neatly each evening with wine and water glasses, napkins and place mats. It was reassuring. We sat about it with our children, my friend’s husband and her mother. My children enjoyed the company of my friend’s mother, and so did I. We relished her wit and grace, as well as her New England cooking. She told us snippets of her childhood in Boston, during the war. On Easter day my daughter and I made a small mossy garden that we put on the table. At the bottom of the actual garden, beyond a low stone wall, was the sea, and a beach where seals bask. We painted hard boiled eggs and rolled them down the cliffs at Dunnet Head, the most northerly point, in a gale that came from every direction.

On Easter Monday we took the boat to Orkney, the spreading islands and lakes across the firth from this end of Scotland. We visited my painter friend, whose tiny house is so full of her paintings that there is no dining table. She prepared us delicious meals, fish cooked in envelopes of paper, home-made pasta pillows that she rolled out from a pasta machine clamped to her worktable, adjusting the side ratchet of it to achieve the right thickness, just as she had adjusted the ratchet on the printing press earlier to get the perfect pressure for printing lino cuts. We hardly noticed the transition from making prints to making food — the improvised precision of art and cookery felt seamless. We ate on chairs about the room.

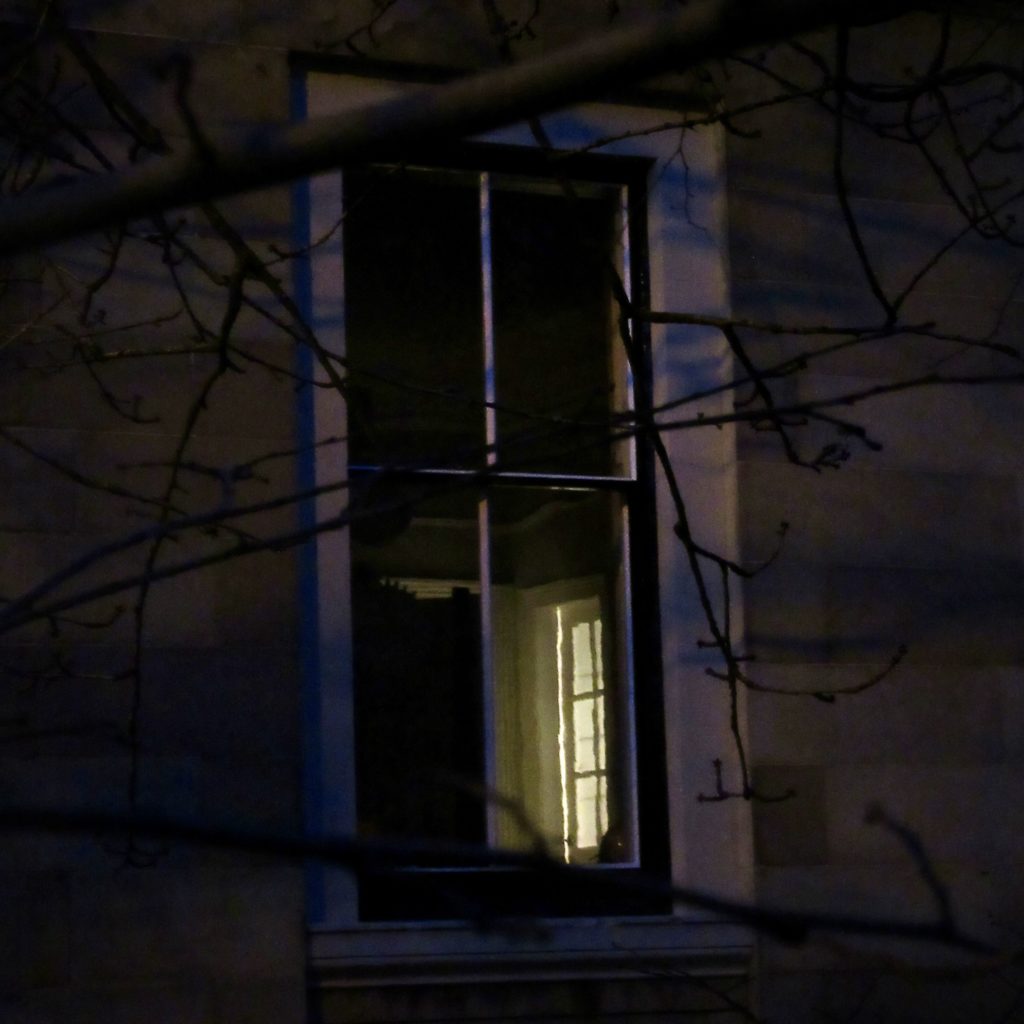

On our last evening in Orkney, also the last night of Passover, we went to visit an ancient tomb by a lake. It was almost dark but you could go freely in and out of the chambered tomb and we sat in the silent arched stone space for a while. The burial chamber was at the bottom of a path through the garden of a house. A light was on in the house. My friend knocked on the door and an older woman answered. She was a friend of my friend and she asked us in immediately, and we sat about her round kitchen table, drinking tea and eating biscuits as the skeletons of the bushes beyond the window blackened against the space of the lake. There was a glint of moon on the water, defining raised ripples on its surface. Inside, the kitchen light was yellow on the table. The kitchen itself was also yellow, thickly varnished pine, darkening with age, reassuringly messy and un-renovated. We sat and talked about the biscuits, and Easter food, and I found myself telling of Easters in Moscow, describing the kulich and pashka — the long white table-clothed trestles outside the church where they were laid out in lines by head-scarved women for the priests to bless by sprinkling holy water. I tried to tell of the sweet mix of spice and dried fruit and grainy curded cheese that went into the pashka, and of how we used to go from house to house for a week after Easter to taste the different baked kuliches and pashkas, fresh from their wooden presses. It was important to try everyone’s — you could devote hours to it, and drinking tea about the tables, in April, and we were so hungry after the long winter.

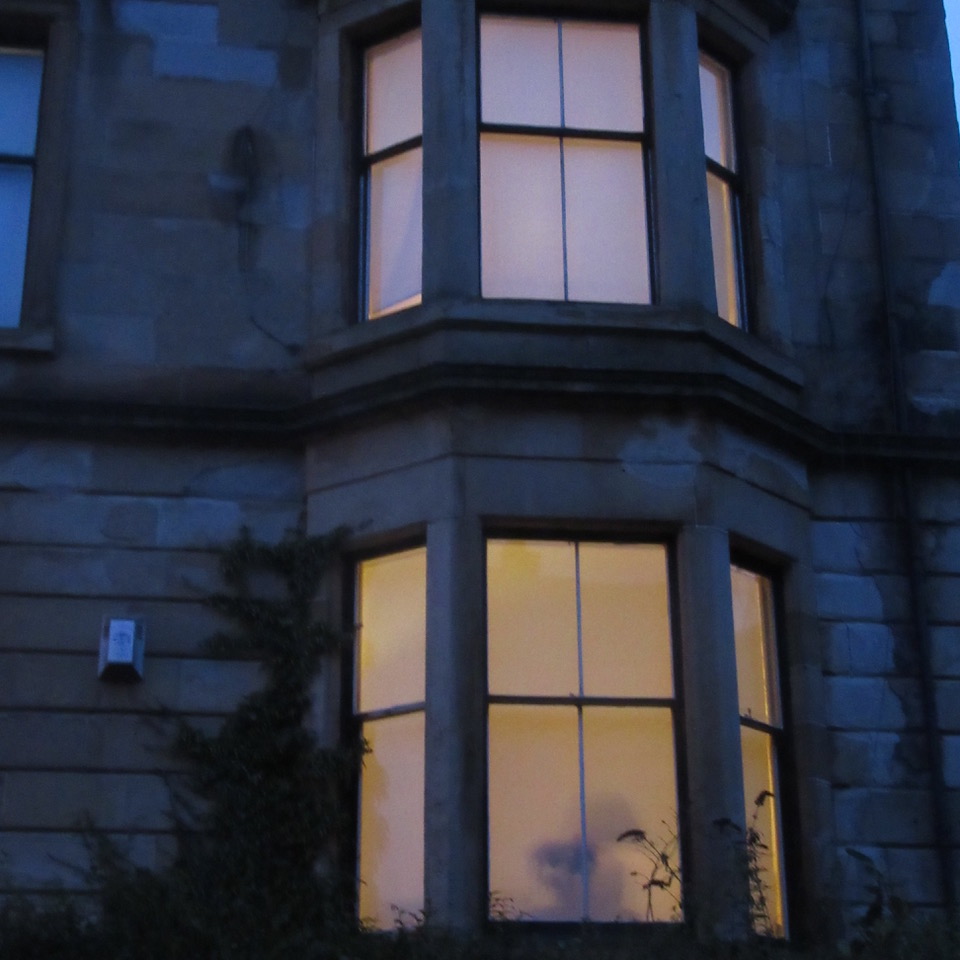

We parted warmly as though we were now all friends. As we left my daughter said “I’ve never heard you tell those stories before”. But the woman’s table had inspired it somehow, the going back, and everyone had leant in and listened. It was very dark once the sun went down. As the vertical light vanished with the closing door there was just the yellow rectangle of the kitchen window and the black silhouette of the house, low reedy bushes, the lake and the grassy curve of the burial chamber. I thought of the long winters here when there are only a few hours of daylight. The woman’s man (she called him that, “my man”, for they had never married) had died early in the pandemic and now she lived with two cats and the burial chamber at the bottom of her garden as her guardians and company.

We took the boat back at six the next morning, and then the long slow train the length of Scotland, down the east coast. We travelled over moorland and through forests of birch. The light was silvery white through the trees, and the birch bark was inflected with shades of pale lilac and the brightest mineral green of lichen. There were also reedy shoots of dark red. It was exciting to see all the trees after the barren treelessness of Orkney and Caithness. The journey took sixteen hours but the pace of it felt right. I was never impatient with it. It felt almost like a long walk.

And then it was Easter again. Orthodox Easter, back in the city. I exchanged email greetings with the friends I cannot see in Moscow and I went to feast on lamb, slow-cooked in brown paper, at the house of a Greek friend. We sat around tables with white cloths, laid out in her living room. I saw people I had not seen for some years. Still these reunions, this novelty, about tables, after the pandemic. And I remembered the Pasternak poem, Earth (1930). It’s almost corny, except it wasn’t when my friend’s mother recited it aloud at the small round kitchen table in Moscow, and it’s not so corny any more now that gatherings still feel sudden and vivid, not a given, this renewed sense of feasts with friends being something crucial yet almost illicit:

Dlia etogo vesnoiu rannei

So mnoi skhodiatsia druzia

I nashi vechera proshanii

pirushki nashi – zaveshchania

chtoby tainaia struia stradaniia

sogrela kholod bytiia.

That’s why when spring arrives

We come together, my friends and I,

And our evenings are goodbyes,

our festive rites — last wishes

so that sorrow’s secret stream

might gently warm the cold of life.*

My Moscow friend Ira’s mother, Sveta, taught me that poem — slowly imparting its rhythm and consonants, sounding it out and at the same time disclosing the objects from corridors and cupboards of a dark Moscow apartment, the furs and old hats that have been stored with camphor, emerging from hibernation into the sudden brightness of spring and its too sharp sensitivity. The evocation of clothes coming out of storage gives way to ritual gatherings of friends about tables, and the knowledge that repetition is reassuring but not a guarantee of permanence. Life and the pain of being sharply alive, a hot stream cutting through the numbness of winter: a poem of endings and not knowing when things will end but being vividly aware that it could be anytime now.

*With thanks to Christine Bird for her excellent translation suggestions

April 11th to April 18

Letter from Dunnet Head: cosmic egg rolling.

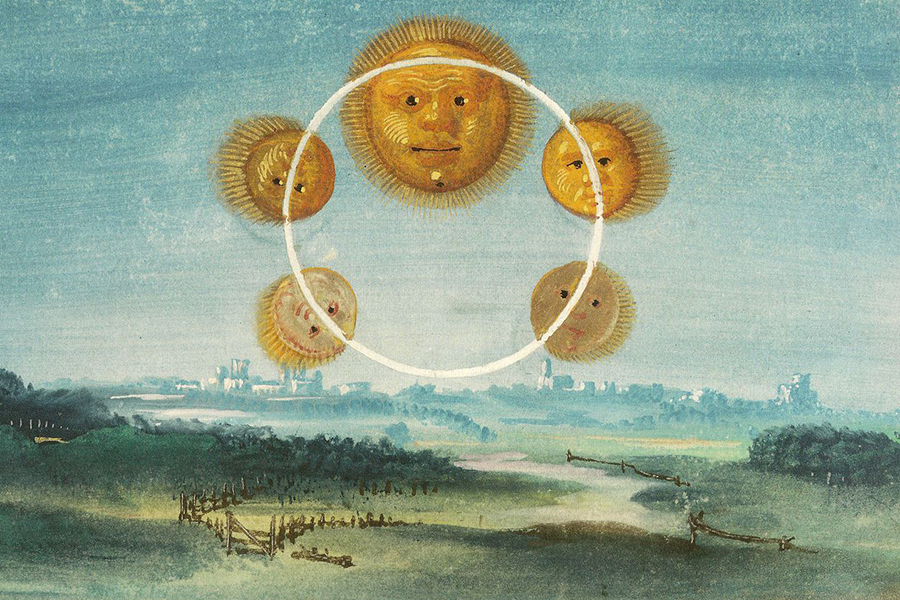

I saw a huge form, rounded and shadowy, and shaped like an egg… Its outer layer consisted of an atmosphere of bright fire with a kind of dark membrane beneath it… From the outer atmosphere of fire, a wind blew storms. And from the dark membrane beneath, another membrane raged with further storms which moved out in all directions of the globe. Hildegard of Bingen, Scivias

Hildegard of Bingen, the medieval mystic and nun, had a vision of the world as a Cosmic Egg. She depicted the earth as a chaotic ball of confusion, contained within an egg-shaped universe. The four winds blow through this universe, concealing and revealing the heavenly bodies. Hildegard believed that the winds would eventually articulate a harmony with this chaotic world and the people in it, establishing calm and clarity, inside and out.

On Easter morning we painted the eggs that we had hard-boiled, then placed them in a box, and drove with our children to the nearby cliffs where the lighthouse stands, on the most northerly point of Scotland. The winds were blowing hard from all directions. The islands of Orkney were hidden by mist and the curved horizon was all sea and sky. We pushed our way through the fat and tearing gales and rolled our painted eggs at the edge of the world, through the slopes of heather, putting our hope in ritual, repetition, and the force of the winds.

March 28th to April 4th

Letter from Glasgow: Poisoned Ground (II), Burial

After I wrote last week’s letter I was thinking about waiting, and not being able to paint, about poisoned grounds and potential. I remembered a field in Ireland with a sign roughly painted by hand saying POISON, and an arrow pointing down. I took a photo of it, over thirty years ago. In London I used to live at the end of a long park that replaced the industrial paint factories obliterated by bombs during the war. The land was deemed too dangerous to churn it up for building on and so a luxurious swathe of un-monetised land was allowed to stretch all the way from Hackney to the river Thames, the long grass growing over it. In the summer it is full of people walking, sitting, having picnics, saris glittering in the sun, along the opaque green slow water of the canal. I was thinking about the relation between poison and colour and paint, of how the best colours are often the most poisonous: lead white, cadmium yellow and red, cerulean.

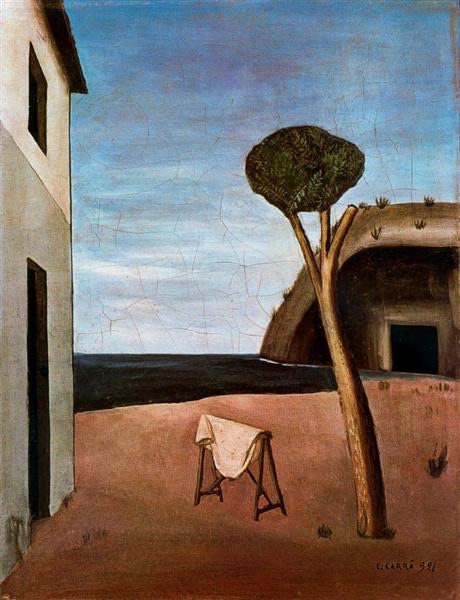

I remembered Antonioni’s Red Desert, his first colour film. The heroine says she is afraid of streets, factories, people and colours. The colours in the film are highly keyed — an intense pitch of yellow, reds and blues set against muted chalky grey monotones of the old world. Antonioni hand-painted objects for the set, in dusty off-whites and greys, like Morandi hand-painting the surfaces of his vases and bowls before setting them up as still life to make paintings from, at around the same time, and in the same country.

In Red Desert, concrete cooling towers and refineries sit like Poussin’s hill towns against classical silhouettes of pine trees. The camera blurs and it is hard to disentangle the two. Italian pastoral becomes industrial wasteland and a new beauty is made from sulphurous yellow smoke, the chrome irridescence of poisoned rivers or orange metal containers. Antonioni looked closely at painting and thought about the colour in his film as a painter might.

In the film, the mother walking the edge of the land which can no longer be cultivated points out a bird to her son, see she says, they learn how to fly out of the way of the poison. There is no sense of a possible return to the pastoral, yet the colours of poison are a visual solace. The landscape is desolate, impenetrable, but the new shapes and colours are also satisfying. The richest paints are the most poisonous. Poisoned ground begins a canvas.

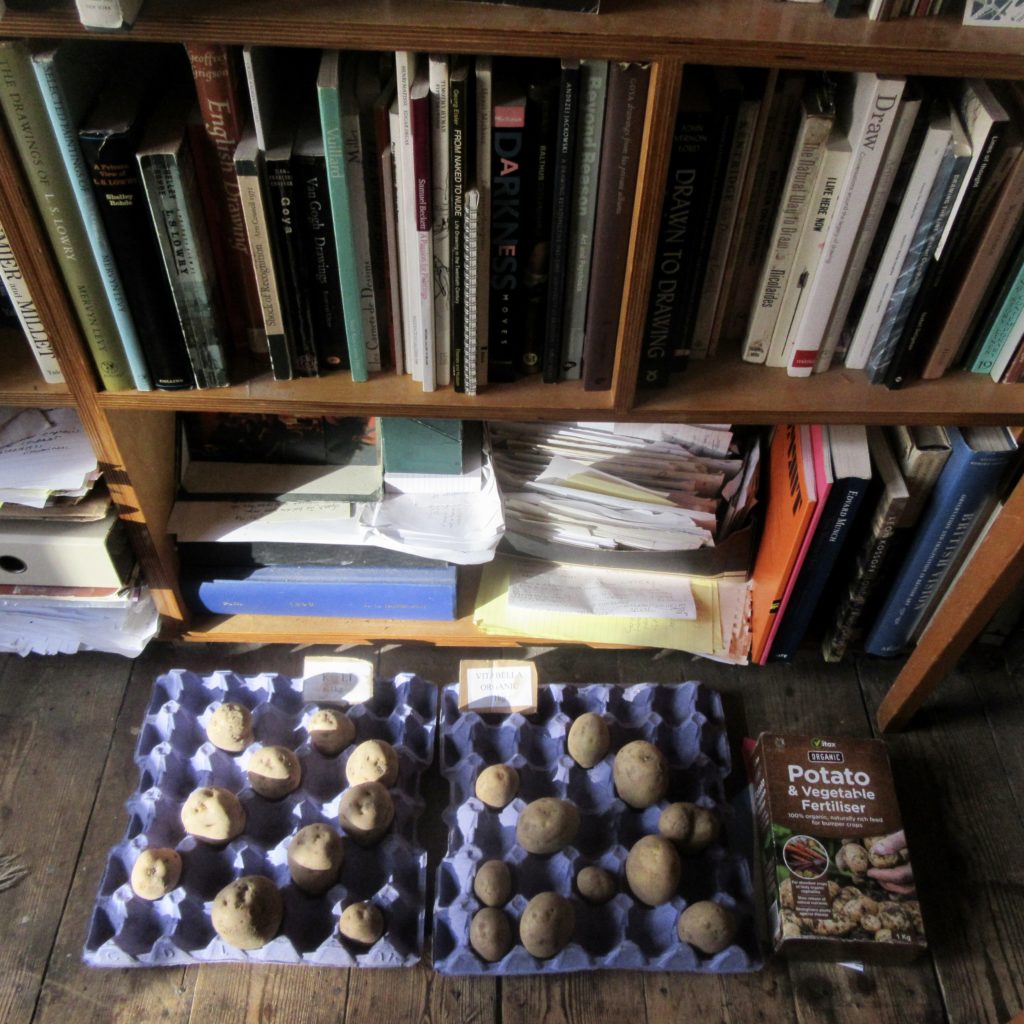

Now I have my own plot of land for growing on, at the edge of an abandoned industrial wasteland. A row of scraped rusting containers in turquoise-blues and reds border the space, wild deer roam the overgrowth among burnt out cars and old mattresses. There are sixty plots on this land that has been reclaimed from an abandoned site, for many years unofficially controlled by a local villain rumoured to be gun runner for the IRA. He used to host dog fights on the space. He said that he wanted to make Glasgow the dog-fighting capital of Europe. It was a dangerous space and the last remaining sheds had been burnt to the ground. In May 2000 Frank McPhie was shot dead by a sniper on the street by his home. The shooting was clean and professional. The single bullet removed from his body indicated a Czech Brno rifle, a popular choice among terrorist gunmen, apparently, for its accuracy. Many of these particular rifles are buried in the ground in Ireland, in hidden weapon dumps.

The council have tried to regenerate the space for more benign purposes. The plots are rented by a mix of locals, refugees and bohemian blow-ins, like me. The locals are important, and help to maintain respect from local gangs who come to smoke and drink on summer evenings. The land is overgrown and wild, with willows and long grass, and suit those of us who have a more relaxed attitude to weeds. I come here intermittently to shovel almost un-shiftable wheelbarrow loads of horse shit until I am sweating and empty-minded, able to see properly again: the trees, the bumpy horizon, the light of sun through mist and the feel of rain beginning. It calms me and wakes me up.

The soil on my plot is rich and black. As I dug it for the first time last year I uncovered odd pieces of bone and brick, crushed metal and plastic, then long reels of exposed 35mm camera film, buried in the ground. I pulled out these crooked ribbons entangled with soil. I thought of my own cartridges of un-developed films twenty five years old, coalescing back to their original darkness. Of how I had always put off getting them developed, how I feared seeing the images that I had shot, leaving that encounter until later, and later, and too late, until the images would have quietly closed over once more. I still have those film cartridges and now I cannot develop them for the proof of disappearance would be too definite. I would have to confront the dark unreadable space of losses incurred by obstinate deferral. I like the thought that some traces of past light might still lie inside the coils of film, hidden from view, but I do not want to disrupt them. I thought of the way that sometimes things can’t be said, or depicted, for a long time. Gestation is an unknown quantity, it demands darkness, hiddenness, but this can be overdone, risking the permanent obliteration of the image, oblivion.

I wondered about poison. The fairy tales where a pricking or a poisoning can put a person to sleep for years — but eventually they awake to a new life, a fairy tale ending, and the awakening cannot happen without the poisoning, and the long sleep. I remembered how I poisoned my own drawing finger, a year ago, while gathering the rich orange berries of sea buckthorn, and of how after the operation to try and flush out the poisoned thorn the Doctor had told me I would never be able to fully flex my right index finger again, the finger that holds my brush or pencil, and I nearly fainted, and then was surprised to realise how much I cared. But slowly my finger regained its responsiveness, and only a slight numbness remains.

And the potatoes that I planted last year in the darkness multiplied, and generated many more, and were eaten. A simple lesson in surprise. Now this year’s seed potatoes sit in my study on top of the paintings I have made from films, from Red Desert and Lord of the Flies, slowly putting out their shoots in the blue March light.

March 21st to March 28th

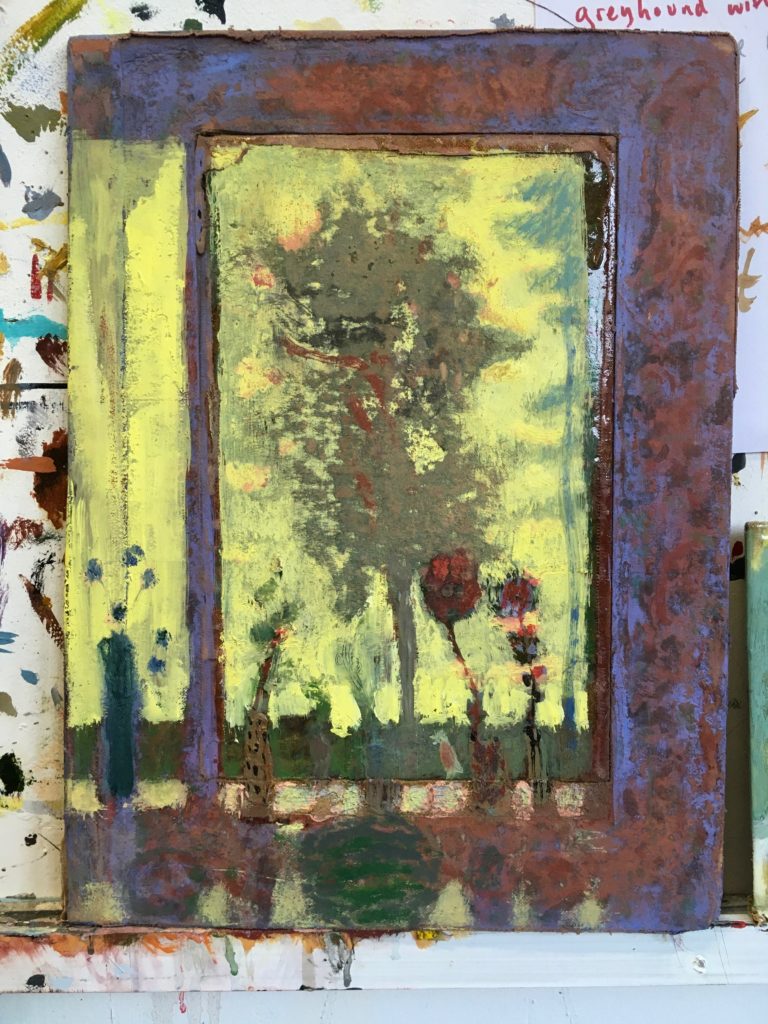

Letter from Glasgow: Poisoned Ground.

Twenty years ago I covered a large canvas with lead white primer. This paint has been banned for over thirty years for its potentially poisoning qualities, but I had a big pot, two and a half litres, bought just before the ban. The linseed oil and pigment paste were separating, so I stirred them round with a stick. The paint is made with shaved coils of lead and has a rich body, unlike any other oil paint. I can still see it falling into itself in thick folds, metallic and yellowish, not unlike the shiny emulsion of raw meringue. I miss it.

A lead ground has to sit on the canvas for six weeks in indirect light before it is ready to be painted on. It is a slow process. First, the building of the stretcher, with saws and chisels — marking the half-way point with a small mallet-shaped gauge and piercing the wood with a bradawl to make lap joints, then attaching lengths of beading to the bars with glue and panel pins. Then stretching the canvas, folding and pinning it, not too tight, with the heavy metal staple gun. Grains of dried rabbit skin are melted in a double boiler to form a pungent viscous glue, applied lukewarm and not too strong (“the texture of apple sauce”), and brushed into the canvas weave. Lastly the lead paint, brushed out in all directions, two coats. And wait.

Six weeks became six months, then years, more than six. The canvas was the largest I had ever made, six foot by five, and as the time grew, so did my doubts about whether I could do justice to that huge, confidently constructed surface, to that open ground — whether indeed I knew what to paint, or how.

I set the canvas aside. Meanwhile I moved to London and back again. I had two children and for a while, no studio. The canvas was stored, blank, against the wall of a small spare bedroom and the children scribbled some spirals on it. When the boy and the girl could no longer share a bed the spare room became my daughter’s room and I had to move the canvas to my new studio, where it stood for six more years. I used to steal glances at it from the corner of my eye, as though avoiding its gaze, but whenever I wanted to paint big I would use paper. I could not face the thought of the painting going wrong on that last lead canvas and I did not know what to paint.

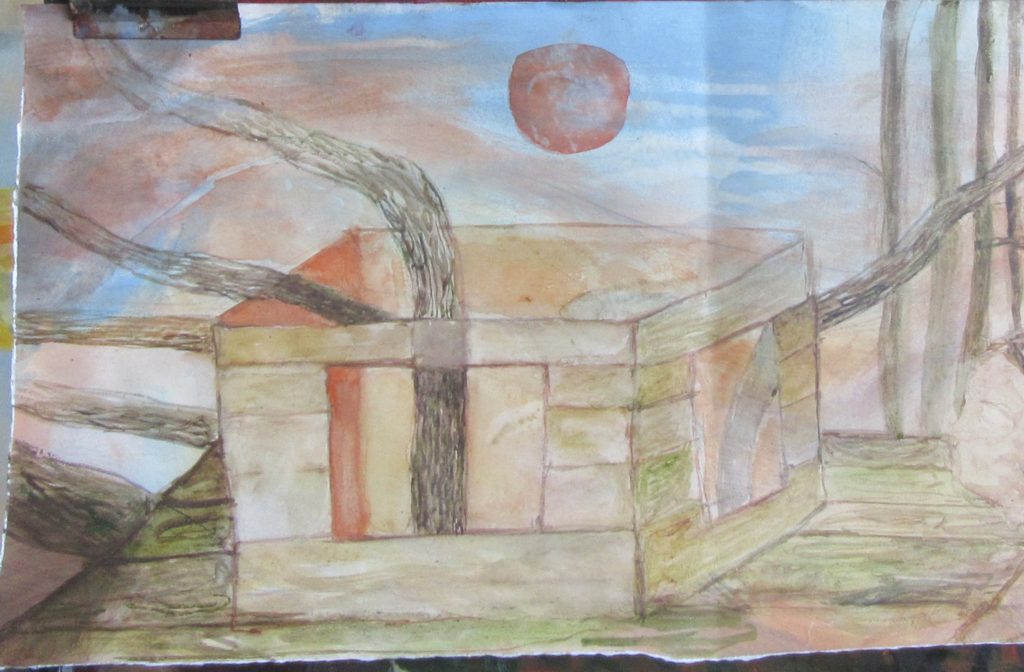

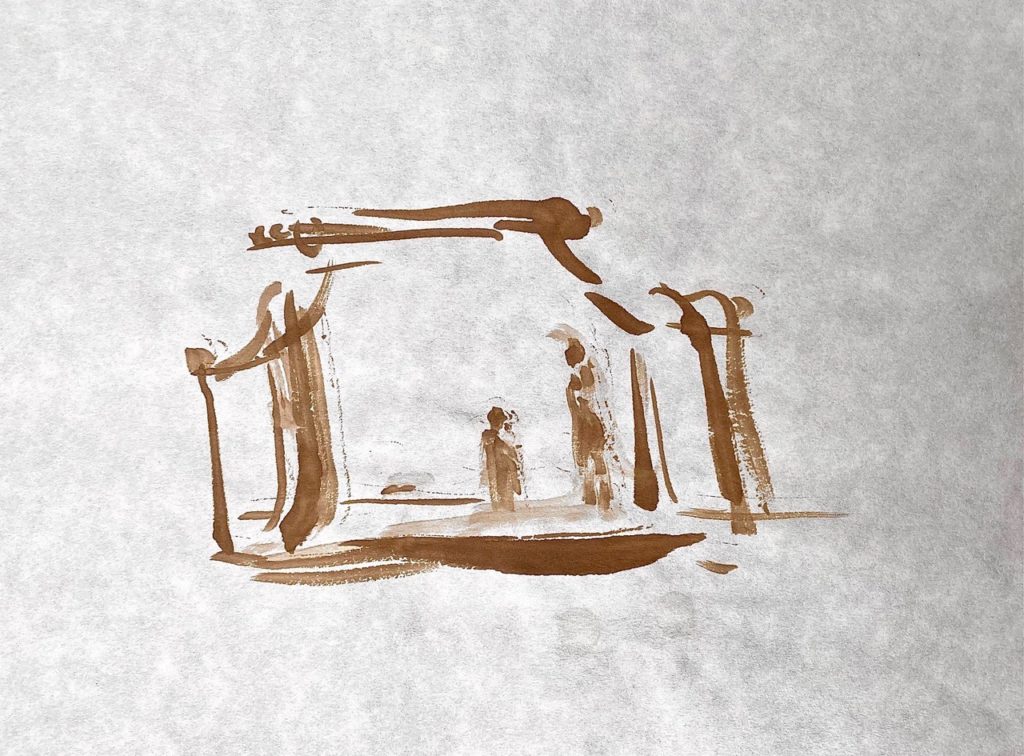

This February, after many months of painting shelters on small strips of old torn-up drawings I suddenly needed more room. Without a thought I pulled out the large canvas, propped it up on two old paint tins, and began. A thin spiralling crack had emerged over the years, like a spider’s web, in the lower part of the paint surface, but that helped me to start. I forgot about the canvas as a structure and it became a space. I painted a stage, a shelter on the ground, with trees. And people — faces in the trees or half-emerging from the trees. They wanted to be painted and I was ready for them. I knew what to do. In the foreground a girl, leaning her head on the shoulder of a strange masked man with a face as red as the sun setting over the water behind. The girl is not unlike my daughter. I’m not sure what will happen next in this landscape that has grown up, after so many years waiting, from this rich and poisonous ground.

March 14th to March 21st

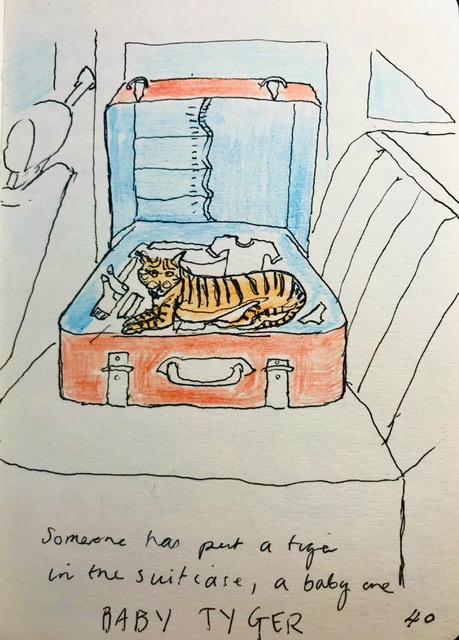

“What else does she like?” Said Mr. Rabbit.

“Well, she likes yellow,” said the little girl.

“Yellow,” said Mr. Rabbit. “You can’t give her yellow.”

“Something yellow, maybe,” said the little girl.

“Oh, something yellow,” said Mr. Rabbit.

“What is yellow?” said the little girl.

from Mr. Rabbit and the lovely present (1962), by Charlotte Zolotow

March 7th to March 14th

Letter from Glasgow: Impossible City (rite of Spring)

The spring is edging in. On Sunday I crossed the river to visit my friend Maud. On the way I met two other friends, both painters. I hadn’t seen them for a long time as their paintings had become successful, much in demand, and they had moved to a bigger flat further out of the city. I was glad for this sudden sighting in their old neighbourhood and mine. I was carrying a lemon for Maud. She had asked for some fruits to paint and so I chose this rather expensive, unwaxed lemon, with curving green leaves on a tall stem. I sniffed it, and held it out for my friends to smell.

They walked me across the bridge to the subway station. As we passed a parked yellow car my friend remarked on the way that my lemon had all but disappeared into the yellow of the car. Her paintings are strong with colour and of course she would see that, all the gradations of yellow. I like the idea of my lemon becoming invisible in my hand as it passed over the slightly more acid yellow background. As I turned to leave them the other painter warned, watch out for the football. There was a big game on he said. Old Firm. That is to say, Protestants v Catholics. A fixture for which this city is famed.

I stood on the platform and the incoming train blew a leaf from my lemon’s stalk. I picked it up. I cradled my lemon all the way to the Southside. Coming out of the station I missed the crossing lights, and heard a low growling. Out from under the flyover came police, and then a crowd of men, a seeming endless procession of men all with bright blue bandanas tied across their faces, just the eyes showing. They were shouting, Fuck the IRA! I stayed where I was and let them cross. The police went before them and followed behind them, holding them in. The procession went on and on up the hill, filling the wide road ahead. I held my lemon and watched them walk into the sun.

My phone went and it was my god-daughter, newly settled in Scotland after growing up in France and New York. I tried to explain the crowd before me to her. I said that they sang lines like We’re up to our necks in Fenian blood. And that the Catholics had a few provocative lyrics of their own, not all romantic longing. She said, so are the Protestants the richer ones? I said no, often they were just as poor if not poorer these days, that was part of the problem. Engels and Marx were on to it early —religion dividing people more surely than class, especially in Ireland.

At last I got to my friend’s house. We sat at her kitchen table and painted. Lemon in lemon yellow gouache. The sun was shining but it was dark in the kitchen so we decided to go to the park. We climbed up the hill to the flagpole into the line of light, through the small crowds of people busy at their games, pushing prams, swinging swings, glittering in this bright about-to-be March sun. At the top of the hill we stood and looked out on the city, filling the whole wide horizon, and the hills behind it, the light flitting across the roofs.

We looked down the path at the people, the trees and the broad boating lake with swans. We felt the sun on our face after all the blank days without it. Suddenly, we heard a noise, a low drone that rose to a rumble, gathering force and enclosing us like a cloud. It was the unseen football stadium at the end of the park. The voice of the crowd stirring, chanting, roaring and pushing like a wave, blasting exultant with a goal.

We could not see them but at once they had got inside the brightness of day. Insisting, growling. The sun itself had moved on and there was ice in the shadowed air. We went back down the hill, past the tree with roots like fat entwined snakes on the surface, past the lit up lichen and moss on the trunks. The game is nearly over, we said. I had better hurry to get ahead of the crowds.

But I was too late. We paused too long and by the time I left my friend and got to the subway it was ten past six and shuttered up. I keep on walking, hopeful that a bus might pass. I walk through the no-man’s land near the river, a territory of breaking-down buildings and wastelands boarded by hoardings, between wide empty roads and the edges of motorways. I’m intrigued, picking my way through a landscape made for cars, to see how far I might get. It is getting dark but I am hopeful, seeing the motorway bridge blocking the space above the river ahead. There must be a lower bridge I think, for people, and buses to cross.

But as I get nearer, the motorway bridge grows enormous, rising up on its tall cement pillars. It becomes vast as a jaw and I am miniscule inside it, hidden and obliterated. The cars speed high above me and below there is nothing but scraps of grass and litter, empty roads and crossings where I must pick my way. And the river itself so black and wide, and I can’t get over. I will have to keep walking, turn upstream or down, a good distance, until I can reach a bridge. So I go back in the direction I came from, downstream, west towards the sun sinking a garish red band against the water. I keep walking, trying to enjoy it, black river and red sun, and the electric blue lights on the buildings by the water, trying to spring my step, until the path becomes high locked railings, and the bridge still a long way off. I must turn back again, back through a car park for a complex of amusement arcade and bowling and cinemas and chain restaurants. I look in at people who don’t seem to be real people, eating in rows. They look as though they are trapped, but I am the one who is trapped — by the car park, the lack of Sunday transport, the town planning and not knowing my way.

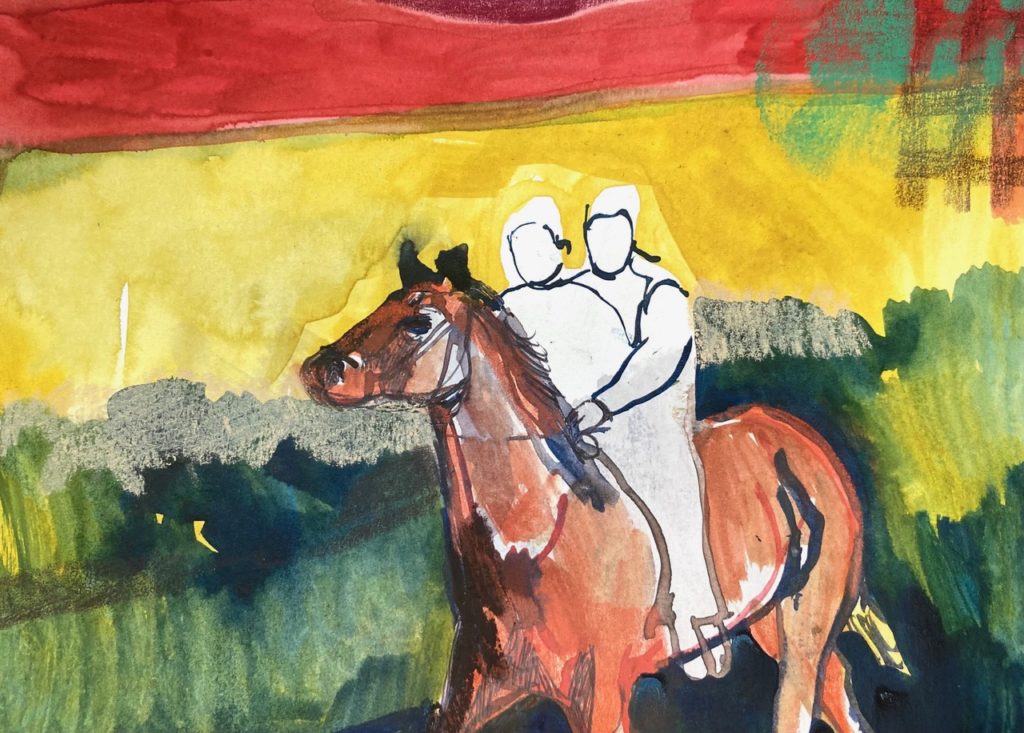

I want to stop, to lie down right in the middle of the car park, and protest: this is impossible! But I have to go on, back through this made-up place and back along the road to find a bus stop. And then, the roar again. And the sound of marching, the sound of hundreds of police marching four or six deep in a long steady procession. Police on horseback too, and behind and in front of them sixteen police vans trailing with grills and flashing blue lights, the lights are flashing silently, and the vehicles move slowly, at the pace of the police feet and the horse’s hooves, taking up the whole of the road, to meet the distant roar of men we cannot see.

I’m exhausted. I find the bus stop and wait for a bus which will take me one stop across the river for £1.70. Where I will need to walk again and wait half an hour for another bus to take me home. I am feeble and tired, and powerless against this city configured for cars. My phone is not smart, and anyway I like to walk without maps: the map denies the pleasure of physically outwitting the city, navigating by physical memory, instinct and guesswork. A digital map would intervene, disconnect me, and be only a sop to inclusivity — a coded proof of the city’s impassability for a person on foot, a timetabled notification of the lack of buses. But I am unused to finding myself at the mercy of the city’s scale. The impossible space of this city of motorways and concrete bridges and wasteland, this un-navigable city. I am not used to such powerlessness.

And when I get home at last I lie on my bed and realise that the city I walked is inside me, all of it, the great black space of water and the dark enormous cavern of the bridge, the empty roads and marching police. All of these are now inside me, that had threatened to engulf me. I can do what I like with them. I hold the impossible city. It sinks down inside to join the other cities and other streets, some of which I will never walk again.

February 28th to March 7th

February 14th to February 21st

Letter from Glasgow: Shadow and Ice

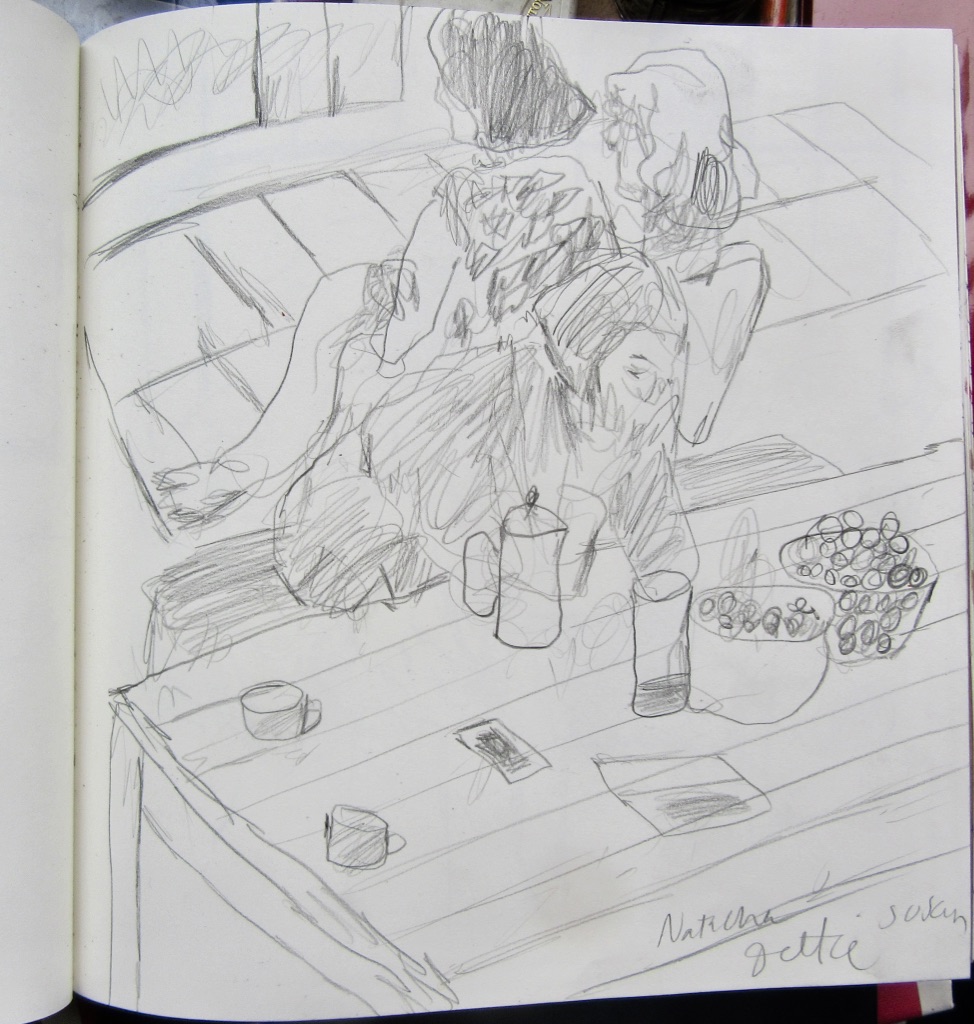

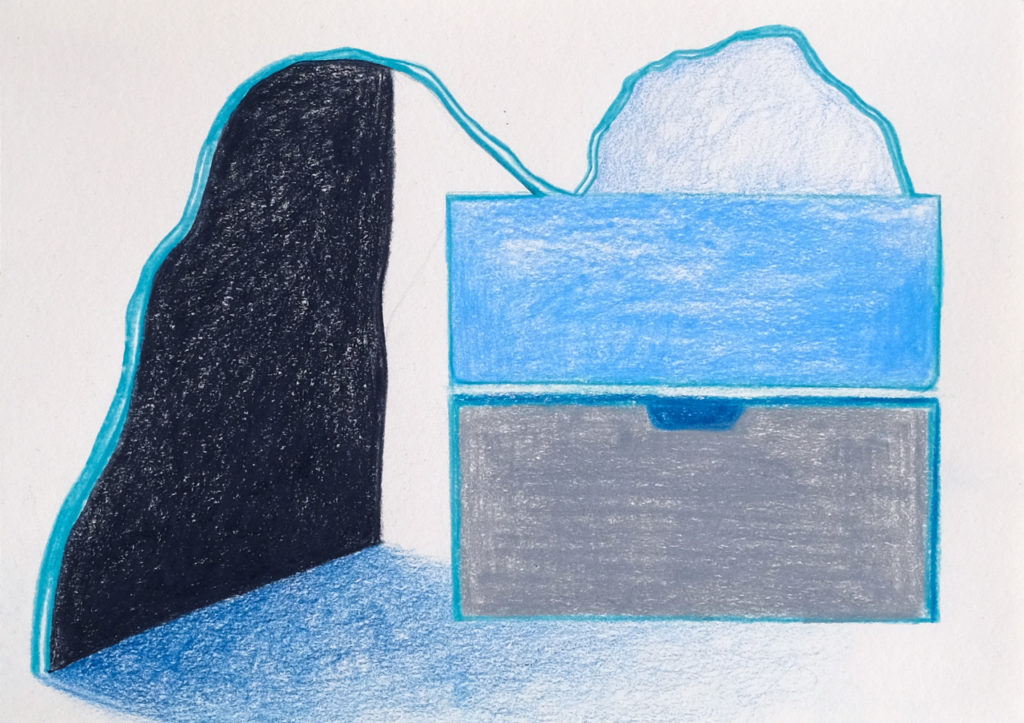

A fortnight ago, Dettie and I each chose photographs we had taken of imaginary mountain ranges for our contribution to the week’s Crown Letter. It was a surprise to us both to find this echo — our miniature details, imagined enormous. Her mountains were made of ice and mine were shadows. Both were subject to the passage of the sun for their fleeting life. Impermanent mountains pointing at the return of the sun after a long winter.

The following day I met Dettie in my dream. I said to her, I can’t understand why I am so tired. Then I remembered. I had given birth to a child in the night. And it had taken ages. A long slow labour, like an endless drive in the dark.

Isn’t it nice to have a child? I say to Dettie. She says that she too has just given birth but she was so tired she has sent her child away to a hot country until they are weaned. I don’t know what came over me, she says. I think she means the child and not the sending away. At that moment a big grown up daughter climbed into her lap.

How strange, we say, to have this late chance. For Dettie and I were born in the same year, 1968, and by any normal reckoning it would be fairly miraculous for us to spontaneously give birth like this.

I woke up, and the child melted from me like ice, like shadow. But the memory of that fierce beginning love clung to me and stayed for at least the rest of the morning.

January 31st to February 7th

Letter from Glasgow: Looking Out

It’s the last day of January. The low red light outside meets the red sap rising inside, in the reeds and branches on patches of unbuilt ground in this city. Red is for readiness. The year is about to kick into place and it is time to wake up. It would be tempting to stay warm inside, wrapped in the dark, looking in, but it is a swift stride from spring to autumn, the time when the lights inside go on again, to pattern the dark. It is as well to wake up now, look out, reach out for whatever presents itself in daylight. And the possibility that this might not be the same thing, that things might be said differently, heard new, seen, as if for the first time, if we allow them.

January 24th to January 31st

January 17th to January 24th

Letter from Glasgow: Still Refuge

My best friend’s mother, who found refuge in London from Iran in the nineteen seventies, used to tell us how in midwinter, in Iran, the seeds of many pomegranates are extracted from their shells to make a glittery red heap, she told us it was to invoke the light of the sun on the darkest day of the year. I pictured vast metallic bowls of shining deep red seeds under pools of light in dark rooms. We never shared such a feast, but she did share her copy of the Persian poet Hafez, opening it at random to let it fall at lines that might have special wisdom or importance for us, which she would seize on with excitement or a resigned nod.

Last Midsummer in Glasgow a Yemeni refugee poet came to my flat, brought by a friend. She recited a poem that held us — it was about the sharpness of light on a table, and we looked at the table we were sitting at and listened to her say how it would be enough to be just half of who we are, for to feel in full, even half of the things that strike us, is more than enough. The brightness of light suddenly entering a room, how even half of such strength would be enough.

We sat about the table listening to the leaps of her voice. I thought about belonging to this table, about points of light, longing and belonging. I was thinking of longing as a sort of lassoing, a sort of looking — casting your gaze, casting out towards, a setting forth. An chiad lar as the setting out, the starting movement of the tune is called in Gaelic pipe music.

And now it is Midwinter, already three weeks past the shortest day. It is time to throw yourself forward, cast yourself off into the year, like a rope — except that here in Glasgow the lid of early morning dark remains firmly on, even as light creeps in at the end of the day. We hold fast to sleep, waking in disbelief at the darkness each morning as if in the midst of night. We lie low in tunnels of sleep for as many hours as we can muster, ten, twelve, staying safe inside the variegated bright motion of dreams.

But it is time to get going, to throw yourself in. I have held off as long as I could. I have celebrated every feast there is — Christmas was just the warm up act, then there was New Year and Russian Christmas a week later and even Old New Year this weekend. The old Orthodox calendar feels more suited to Scotland for it is only now that the sun begins to show itself, a slow bleed. It finally entered the kitchen this morning, and my friend who was staying said, this flat is like St Petersburg, or really she meant Leningrad, for it was the old flats we had known from the 80s and 90s that she was thinking of, the decrepitude, the chaos, and the high ceilings.

This morning, for the first time, a thin line of light enters the dark corner kitchen, unfolding the space, opening it up. And on the radio, the delicate dirge of Gavin Bryars’ found recording of a homeless man in a London shelter singing — Jesus’ blood never failed me yet .. on a loop. A daring choice by Kate Molleson for Radio 3 breakfast, I’ve heard it before but late at night, Monday at ten past 8 it is more likely to be Bach, Purcell or maybe Britten. The light is a slow bleed and Jesus’ blood, never failed me.. yet, turning round and round.. The melancholy of this pale mid January morning, and my friend saying this is St Petersburg.